‘Objective’ tour at Auschwitz largely ignores the Jews

For two hours, a museum guide spoke of how severely the Poles had suffered at the hands of the Nazis, while Birkenau was quickly brushed over.

By Faye Lincoln

JNS

Aug 1, 2025

In 1944, during World War II, my parents, a young married couple, were transported to the Nazi death camp Auschwitz. One of my mother’s first sights was of Dr. Josef Mengele, the “Angel of Death.” Mengele allowed her to survive even though she was helping a young, orphaned boy, who ultimately died. One of her indelible memories was of refusing to throw Jewish bodies into a mass grave, defying the orders of a German soldier. Yet my parents survived.

Before my recent visit to Auschwitz, I was prepared to be grief-stricken, expecting a guide to delve into the atrocities suffered by the Jewish victims. Instead, I was incensed at the lack of empathy and respect for the horrors that took place against Jews in this death-haunted outpost.

Our museum tour guide “minimized” the experience of the Jews by replacing much of the camp’s Jewish history with a focus on what happened to the non-Jewish Polish people.

When the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939, 3.5 million Jews lived there, the largest concentration in any country. The Nazis refurbished Polish military barracks into Auschwitz I, which began as a prison camp but then exploded into a sprawling complex. This death center grew to include Auschwitz II, also known as Birkenau, where Jews were gassed in a ghastly industrial program, and Auschwitz III, also known as the Monowitz factory center. When the war ended in May 1945, a total of 1.1 million Jews had died: worked, tortured or gassed to death.

With more than 44,000 established camps, subcamps, ghettos and other sites of incarceration, the German Nazis killed more than 6 million Jews. In addition, the Reich killed an extraordinary number of Poles, Russians, Romanians and other prisoners. Not once did our tour guide mention the enormity of these numbers.

The Nazis were clear about their goal. “Jews are a race that must be totally exterminated,” said Hans Frank, who headed the so-called “general government” of Nazi-occupied Poland, in 1944. Yet here I was, in 2025, on an official Auschwitz tour, listening to the details of how the Nazis deported “140,000 to 150,000 Poles, 23,000 Romanians, 15,000 Soviet prisoners of war and 25,000 other prisoners from other ethnic groups” to the slave labor camp.

What about Jews?

While the camp originally housed 10,000 prisoners, it was enlarged to hold 30,000 individuals, with up to 1,400 people living in each barrack. Yet, unmentioned by our guide was that more than half of the prisoners were enslaved Jews who were treated brutally, and that more than a million Jews were never interred because they had been dispatched directly to gas chambers for extermination, and then cremation to hide the evidence.

For two hours, our museum guide spoke of how severely the Poles had suffered at the hands of the Nazis. Unsanitary and crowded conditions brought disease and death. Nazi soldiers sent sick prisoners to a single hospital barrack, not to be treated, but to die. To set an example for others, soldiers routinely hanged Polish prisoners from the gallows or shot them in the courtyard. Camp “physicians” became murderers, experimenting on Polish women without anesthetics to test sterilization techniques. All of this is correct, but missing from the tour explanation was that gas chambers were used to kill as many as 2,000 Jewish people each day using the poisonous pesticide Zyklon-B.

On the tour, we were told that the Nazis believed Polish citizens should not be educated, but used for labor. We were not told that the Jews were destined to be worked to the point of death, and then sent to be gassed.

The museum had hundreds of pictures hanging on the barracks walls honoring Polish criminals and dissidents. The photos included intellectuals and professionals brought to the camp, as the Nazis saw these groups as being antagonistic toward the Third Reich. Yes, the Nazis imprisoned university professors and professionals, including doctors and lawyers. At the time, 60% of Poland’s lawyers and 40% of its doctors were Jewish. A 1941 Jewish Daily Bulletin reported that all members of the Polish bar had to prove they were neither Jewish nor of Jewish descent. Yet only a few of the photos in the barracks were of Jews.

Why, I wondered, were we not hearing more about the history of the Jews who had died here? Where had they been housed? Surely not in the now-pristine brick barracks. Yes, on the tour, we viewed depressing displays of their stolen personal belongings: shoes, pots and pans, prayer shawls and eyeglasses. Nazi soldiers cut women’s hair and sold it to make fabric and clothing. They shipped these goods to the Third Reich for the Germans’ personal use. I could not help feeling that our guide’s narrative sounded clinically objective and sterile after repeating the ghastly details daily. But for the visitor, the experience is piercing, and, to me, the missing empathy seemed critical.

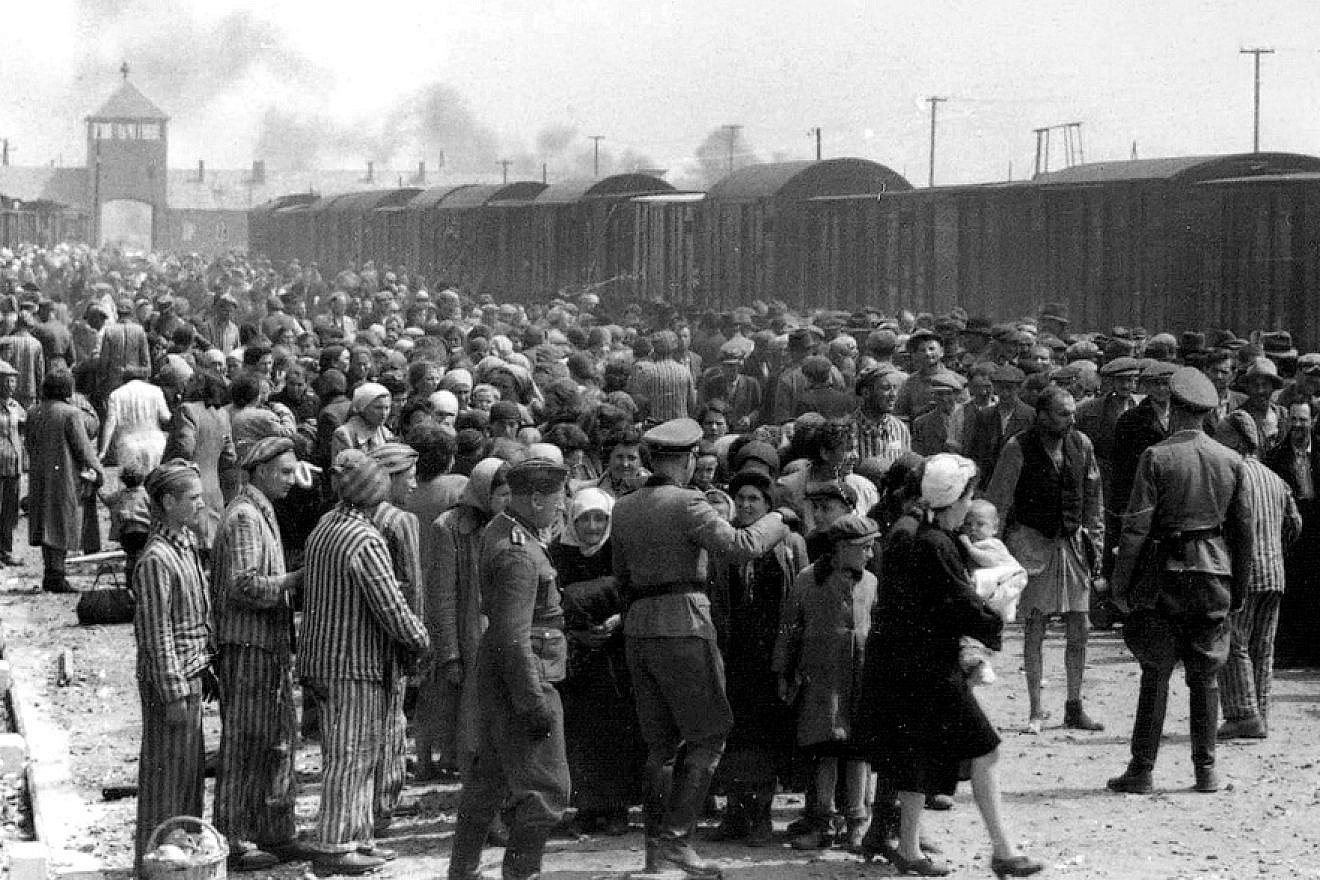

The most impactful portion of our tour was at Birkenau, the death camp. Here was where 1.1 million Jews arrived by rail in cattle cars and were immediately made to strip naked. Some, adjudged capable of work, were assigned to one sector of this camp as slave labor until they died of exhaustion. But most were sent to the “showers” to be gassed and then incinerated in the crematoria.

The Birkenau part of our tour lasted a mere 15 to 20 minutes as the guide explained the history of one of the worst atrocities in human history. Unlike Auschwitz’s brick barracks, Birkenau’s shacks were small, wooden and dilapidated, with endless rows of cramped bunks. At any given time, as many as 150,000 people were imprisoned at Birkenau as slave labor, compared to the 30,000 at Auschwitz I. Examples of humanity and kindness existed among these prisoners, but such stories were not shared on our tour. At the end of the war, the Germans destroyed and left in ruins the four enormous crematoria at the far end of the camp, never to be inspected by the world, while the majority of barracks in the camp were torn down by Poles for wood to build homes.

With the physical structures largely gone, it is up to the official guides to recreate and retell that awful reality. This, it seems, our guide failed to do. Instead, she informed us that she had to remain “objective.”

Objective? How can one possibly remain objective in such a place? Our Auschwitz “museum” guide had glossed over Jewish history by focusing on its non-Jewish Polish story. Thousands of people visit Auschwitz daily, while only a few hundred people visit Birkenau. Most people visiting the complex might not even know to visit Birkenau.

My outrage heightened as I left Birkenau, seeing only a tiny educational book and gift shop, unlike the enormous bookstore, gift shop and restaurant at Auschwitz. Restrooms at Auschwitz were numerous and free; Birkenau’s were small, cramped and required visitors to pay for their use. At Birkenau, all dignity for the memories of yesterday’s dead seems to have been lost.

My impressions are not unique. Increasingly, visitors to the Auschwitz complex report that the compelling Jewish tragedy of the camp has become a footnote to another story.

To rightfully emphasize the history of the Nazi death camps, thousands of people from all over the world should continue to participate in annual remembrance events at Birkenau, including the March of the Living and JCC Krakow’s Ride for the Living. These organized activities help counterbalance the “whitewashing” of Auschwitz’s largely Jewish history by indelibly honoring those who survived, as well as the memory of 1.1 million Jews who died there.

No comments:

Post a Comment