The Greenland situation explained

There were some fraught days when U.S. President Donald Trump was threatening to use a big stick to take the island away from the Danes, but the situation seems to have settled down.

By Clifford D. May

JNS

Jan 29, 2026

Readers of a certain age will recall the late, great Tina Turner introducing her iconic performances of “Proud Mary” by informing her audience: “We never, ever do nothing nice and easy. We always do it nice and rough.”

U.S. President Donald Trump could say the same about his style of policymaking. Greenland is the most recent example.

Trump understands that the Arctic island is essential for America’s national security and that of Europe as well. Look at the globe from above. The shortest routes for long‑range Russian or Chinese missiles targeting the United States pass over the polar region. There’s also the Greenland‑Iceland‑UK (GIUK) gap, a key chokepoint through which Russian submarines must pass to reach the Atlantic.

Because Greenland is a self-governing territory of Denmark, an American ally, and because Trump is the world’s greatest dealmaker, it seemed to me from the start that if any international dispute could be solved with a deal, it’s this one.

Nevertheless, there were some fraught days when Trump was threatening to use a big stick—tariffs or even military force—to take Greenland away from the melancholy Danes. Could that have just been a nice-and-rough negotiating tactic? Demand the stars, settle for the moon?

Readers of a certain age will recall the late, great Tina Turner introducing her iconic performances of “Proud Mary” by informing her audience: “We never, ever do nothing nice and easy. We always do it nice and rough.”

U.S. President Donald Trump could say the same about his style of policymaking. Greenland is the most recent example.

Trump understands that the Arctic island is essential for America’s national security and that of Europe as well. Look at the globe from above. The shortest routes for long‑range Russian or Chinese missiles targeting the United States pass over the polar region. There’s also the Greenland‑Iceland‑UK (GIUK) gap, a key chokepoint through which Russian submarines must pass to reach the Atlantic.

Because Greenland is a self-governing territory of Denmark, an American ally, and because Trump is the world’s greatest dealmaker, it seemed to me from the start that if any international dispute could be solved with a deal, it’s this one.

Nevertheless, there were some fraught days when Trump was threatening to use a big stick—tariffs or even military force—to take Greenland away from the melancholy Danes. Could that have just been a nice-and-rough negotiating tactic? Demand the stars, settle for the moon?

Maybe, but to my relief (and that of the stock market) at the World Economic Forum in Davos last week, Mark Rutte, the extraordinarily capable secretary general of NATO, came up with a “framework” for a long-term agreement that appealed to the American president. “This solution, if consummated, will be a great one for the United States of America and all NATO nations,” Trump exulted on Truth Social.

If he had his druthers, Greenland would become an American territory like Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa and the U.S. Virgin Islands—the latter, it so happens, purchased from Denmark in 1917 for $25 million in gold coin.

But if Washington now leverages an expanded authority to detect, deter, and, if necessary, defeat threats on the world’s biggest island while Denmark retains sovereignty, history will record that as a significant Trump achievement.

And would it not be better—more Trumpian, really—for the United States to make the key decisions on Arctic defense, while other NATO members pick up most of the checks?

Additionally, four in 10 Greenlanders are government employees. Moving them from Copenhagen’s payroll to Washington’s strikes me as not ideal. As to the notion that the island should become America’s 51st state, based on the evidence at hand, Greenlanders are more likely to vote like Minnesotans than Alaskans.

I think it’s always interesting (and occasionally, useful) to know a bit about the history of lands involved in conflicts and controversies with the United States, as Trump told a group of oil executives: “The fact that they [the Danes] had a boat land there 500 years ago doesn’t mean they own the land. I’m sure we had lots of boats go there also.”

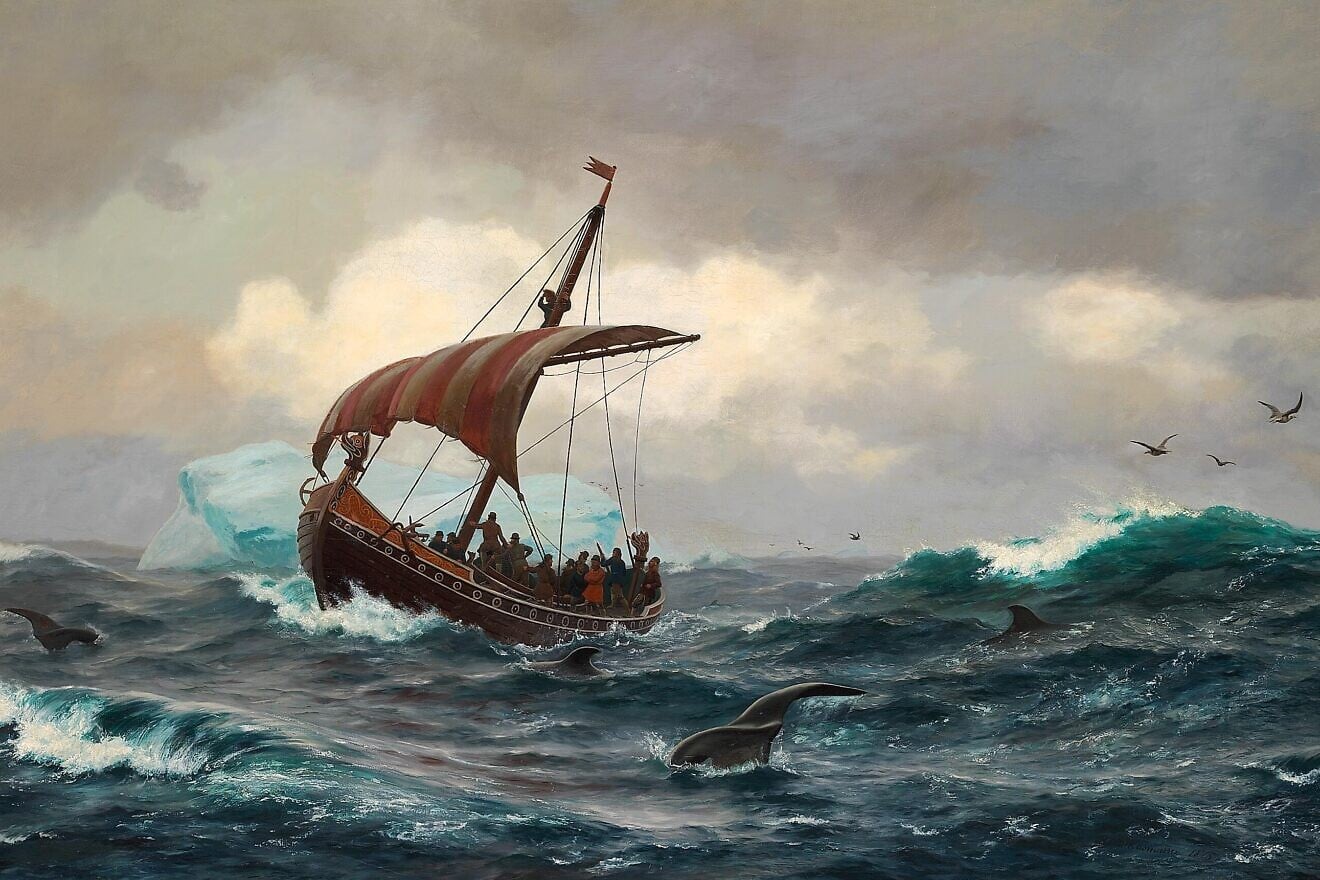

Here’s the backstory: Norse settlers, led by Erik Thorvaldsson—his madcap Viking buddies nicknamed him “Erik the Red”—reached southern Greenland around 985 C.E. That was a couple of centuries prior to the arrival of the Thule Inuit, ancestors of most modern Greenlanders. The Inuit had migrated from northeast Asia across the North American High Arctic. The fact that tribes with only primitive tools and weapons could survive in these environments and climates is a testament to human adaptability.

Speaking of climates, between 800 and 1300 C.E., there was the Medieval Warm Period, during which southern Greenland experienced temperatures mild enough to allow for limited agriculture, as well as grazing sheep and cattle.

Erik the Red: "The people will be more easily persuaded to move there if the land has an attractive name."

That said, the bright idea by “Erik the Red” of naming the island “Greenland” was as purposely deceptive as Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s (D-N.Y.) “Green New Deal.” Back then, ice covered about 80% of Greenland. That percentage hasn’t changed—bovine flatulence and CO2 emissions from soccer moms’ SUVs notwithstanding.

The Little Ice Age began in the 14th century and continued until the mid-19th century. That chill was among the reasons that in the 15th century, the Norse settlers disappeared—most likely, headed for the balmier climes of Iceland and Scandinavia.

Fast-forward to 1940: The Germans conquered Denmark in a matter of hours. America sends troops to Greenland. After World War II, Norway became a founding member of NATO.

In 1951, the United States and Denmark signed the Defense of Greenland Agreement. During the Cold War, more than 6,000 Americans were stationed on the world’s largest island.

Today, only about 150 members of the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force operate Pituffik Space Base in northwestern Greenland, focusing on missile warning.

The prospect of a new Greenland deal prevents what some argued could have been the collapse of NATO. I’m pro-NATO, but I think Trump is correct to insist that America’s allies be partners contributing to the collective security, not dependents.

Among the free-riders: Spain, Belgium and Canada.

And the United Kingdom needs to be called out. British Prime Minister Keir Starmer has been eager to surrender another strategically vital island: Diego Garcia, in the Chagos Archipelago in the Indian Ocean.

Since the 1970s, the United States and the United Kingdom have maintained a military base on Diego Garcia. But as an act of atonement for the sins of British imperialism, Starmer wants to surrender sovereignty to Mauritius, a speck of an island nation 1,300 miles away, east of Madagascar, which is increasingly being pulled into Beijing’s empire.

Trump characterized that as “great stupidity.” British conservatives, to their credit, are trying to block the giveaway.

Sometimes, one can say about a Trump policy what no one would say about a Tina Turner song, but which a wit once said about the music of Richard Wagner: “It’s better than it sounds.”

Originally published in “The Washington Times.”

No comments:

Post a Comment