Why the Dreyfus case matters now more than ever

Canceled because of its director’s crime, the best film made about the “Affair” belatedly arrives in the United States, posing difficult ethical, artistic and political questions.

By Jonathan S. Tobin

JNS

Aug 15, 2025

The public humiliation of French Army Capt. Alfred Dreyfus. This image was created to promote an exhibition on the Dreyfus Affair at the Maltz Museum.

For as long as people have cared about the arts, the question about whether one’s personal foibles or even crimes are more important than their work has always bedeviled audiences and critics. Perhaps no artist has embodied that dilemma more fully than the film director Roman Polanski, whose 2019 film “An Officer and a Spy” about the Alfred Dreyfus case 130 years ago in France is belatedly receiving a first screening in the United States with a limited engagement at the Film Forum in New York’s Greenwich Village.

The 91-year-old Polanski, who survived the Holocaust as a boy, is responsible for a long list of highly respected films, such as “The Pianist” (2002), “Chinatown” (1974) and the psychological thriller “Rosemary’s Baby” (1968), all of which won Oscar awards. His second wife, actress Sharon Tate, was murdered by the Charles Manson cult in 1969 in one of the most publicized crimes of the 20th century.

But his legacy is forever linked to the fact that he has himself been a fugitive from American justice since 1978, when he fled the country the day before he was to be sentenced by a California court for drugging and raping a 13-year-old girl.

Polanski had agreed to a plea bargain that would have had him confined to a psychiatric facility for three months; however, he learned that the judge was going to reject it and sentence him to 50 years in jail. He escaped to France, safe from extradition because of his French citizenship, eventually remarrying, raising a family and resuming his career, as well as continuing to win accolades for his work.

A fugitive from justice

Since then, Polanski has been accused by other women of abuse during his time in Hollywood in the 1970s, but he has always seemed to consider himself more a victim, whether of the justice system and especially the press, than a criminal. He managed to avoid any accountability until 2009, when he was arrested in Switzerland at the request of the United States. But a Zurich court rejected the American extradition request and freed him. Though reportedly the Interpol alert issued in 1978 that had limited his travel to France, Switzerland and Poland is still in effect, he is no longer on its wanted list.

The difficult question of whether his crime should mean that his work shouldn’t be seen has been revived with the New York showing of the French-language “An Officer and a Spy,” which was originally shown in France under the title “J’ACCUSE.” Indeed, the Film Forum posted a trigger warning about it on its website, acknowledging that many believe that the director’s work ought not to be shown because of his sexual-assault conviction and other allegations.

The film won a raft of important European film awards, including multiple Césars, known as the French Oscars. But in the wake of the rise of the #MeToo movement in 2017, some denounced the acclaim it received, and it didn’t get a distributor in the United States. Nor was it ever released on home video in the American market. While many in the film industry had rallied to his defense during his Swiss imprisonment, the ranks of those actors and fellow directors willing to speak up for him either out of friendship or respect for his artistic genius have thinned.

The debate about Polanski and this film has been exacerbated by the fact that he was open about saying that he identifies closely with the fate of Alfred Dreyfus, the French Jewish military officer falsely accused of treason and sent to Devil’s Island before eventually being vindicated. Dreyfus, however, was innocent. Polanski was clearly guilty of the crime for which he was to be sentenced. The comparison is absurd—an insult to the memory of Dreyfus and an illustration of the director’s insufferable narcissism.

Though Polanski may be deplored as an individual, the film is certainly worth seeing. It is based on the brilliant novel An Officer and a Spy by the British author David Harris, who was encouraged to write about the subject by Polanski. Both the book and the movie provide a good introduction to a case that has been the subject of innumerable volumes as well as a few cinematic adaptations. Indeed, if one were to see just a single film about the case, it would have to be this one. It’s far superior to any previous such effort, including the 1937 “The Life of Emile Zola,” the 1958 “I Accuse” and the 1993 “Prisoner of Honor,” all of which had some virtues.

A man of honor

Harris’s novel and Polanski’s film are different in one way because the main protagonist of the story related in the screenplay (co-written by Harris and Polanski) is not the victim, Dreyfus. Instead, its focus is Georges Picquart, the man who—though largely forgotten by history—did more to win Dreyfus’s freedom than anyone else involved in the controversy.

What makes that so remarkable is that Picquart, then the youngest colonel in the French army and who had been his instructor at a staff college, neither liked Dreyfus or Jews, in general. A rising star in an institution where antisemitism ran rampant, the cultured Picquart was typical of his class and despised the bourgeois, unsociable and rich Jewish officer. After being appointed the head of military intelligence in 1895, he uncovered what at first he thought was a second German spy, another French officer named Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy. He soon uncovered definitive proof that there was only one spy, Esterhazy, and that Dreyfus had been wrongly convicted.

Told to bury the damning evidence, Picquart—a man of honor, even if he was as hostile to the Jews as his peers—refused to do so. As a result, he was demoted, isolated and eventually imprisoned on other false charges. But by bringing the truth to the attention of the Dreyfus family and to French author Emile Zola, whose famous essay “J’Accuse … !,” revived the debate about the case, the path to the falsely accused victim’s redemption was set.

A monument to French Jewish artillery Capt. Alfred Dreyfus in Tel Aviv, Nov. 30, 2018.

Polanski’s film unravels how Picquart learns the truth, and how both his superior officers and one of his subordinates—the despicable Major Hubert-Joseph Henry, who had forged some of the original evidence against Dreyfus and perjured himself in court—turned on him for not going along with their lies. Each step of the way in what is an even more complicated story than superficial students of the case may know—from the opening scene depicting Dreyfus’s appalling degradation in the courtyard of the École Militaire with a mob screaming for his death and that of the Jews, to Picquart’s astonishment at the dishonesty of his fellow officers to the trials where the truth comes out but is still denied by the courts—is heartbreaking. Indeed, so convincing is the account of how the plot unraveled that it’s almost possible to forget that we know how the story will turn out.

Of particular note is the performance of French actor Jean Dujardin, best known to international audiences for winning an Oscar for his role in the 2011 silent film “The Artist.” His Picquart manages to be both an imperturbable and somewhat stoic military type, yet so invested in the idea of integrity and honesty that he was willing to destroy his own career and life, as well as that of his married mistress, Pauline Monnier (played by Polanski’s real-life wife, Emmanuelle Seigner). Louis Garrel similarly embodies the desperation of Dreyfus, a man caught in a nightmare he knows is rooted in the Jew-hatred of the country he loves.

The case split France down the middle and illustrated scholar Ruth Wisse’s teaching that antisemitism is a way to weaponize hate against Jews to achieve a political end. In the case of Dreyfus, the Catholic army establishment desired to achieve dominance in a republic where arguments that had begun during the French Revolution a century earlier remained unresolved. As we learn, it’s not the justice system that achieves the officer’s vindication as much as it is a shift in the country’s political mood that brought to power Dreyfus and Picquart’s advocates.

Though six years old, the movie is particularly timely at a moment when, once again, hatred is on the rise and lies about the Jews—this time not an isolated French officer but the Jewish state itself—are similarly being concocted out of whole cloth and spread by those who should know better.

Polanski, and perhaps some of his admirers, seem to think that his status as a survivor provides some insight into his behavior and maybe even something like a pass for his misdeeds. Polanski’s childhood trauma helped form him. His Catholic mother died in Auschwitz, and his Jewish father survived Mauthausen, while the 10-year-old Polanski escaped from the Krakow Ghetto and was then hidden by Polish Catholics.

Still, however much we may sympathize with that aspect of his biography, it can’t grant him absolution for abusing girls and young women. Nor does his great art mean that we should ignore his crimes.

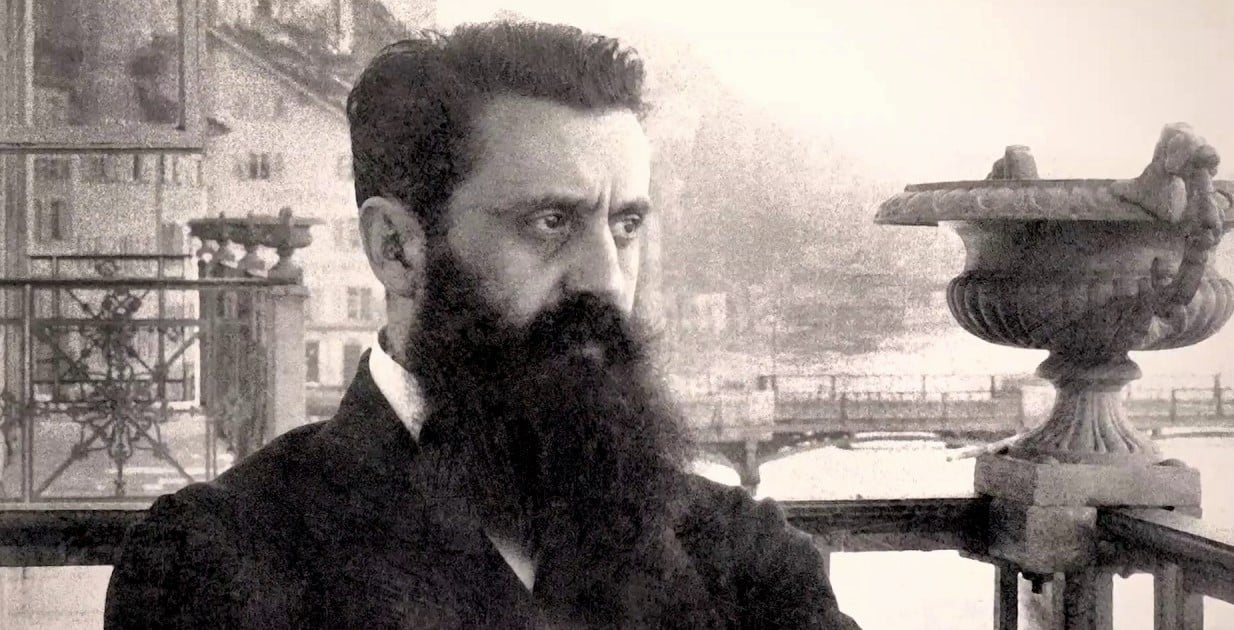

Austro-Hungarian journalist and founder of modern-day Zionism, Theodor Herzl.

An unanswerable question

The question of whether we can separate the artist from his art is as unanswerable with respect to Polanski as it has been for anyone else whose personal behavior or beliefs were repugnant but produce work that is not only admired but also elevates humanity. It’s worth noting that the music of the vicious antisemite Richard Wagner, whose operas still hold the stage, was loved by Picquart as well as Theodor Herzl, the founder of modern Zionism. Herzl witnessed Dreyfus’s degradation and was in part influenced by the case during the period when he was writing his seminal book The Jewish State. It’s easier to think of the world as divided between good and bad people, and that we must always shun the latter. But the truth is that bad people can create good art that helps inspire good people to do great and noble things.

I understand and sympathize with those who believe that Polanski should have spent the last half-century rotting in jail rather than living the good life in Europe making movies. And yet I also understand and sympathize with those who would answer that the world would be much poorer without the art that Polanski created during those years, in particular, films like “The Pianist” and “An Officer and a Spy,” which do so much to inform and elevate our discourse on important issues like the Holocaust and antisemitism.

The questions this version of a well-known story asks pointedly are those we must ask ourselves today. Are we willing to stand up against mobs spewing hate against Jews like those who howled at Dreyfus? Is it possible to defy a widely believed consensus that holds that the Jews are guilty of terrible crimes because it is so much easier to go along with that prejudice?

Georges Picquart’s answer to those questions, like that of righteous gentiles in every generation, was “yes.” And while for a time he was crushed by the enemies of the truth, eventually, he and Dreyfus won. Both were returned to the army, with Picquart promoted to the rank of general and made Minister of War by Dreyfusard politician Georges Clemenceau (who would lead France to victory a decade later in World War I).

The two men who were the heroes of the story never became friends; indeed, they actually resented as well as respected each other. But as the film’s final scene relates, Dreyfus understood that his freedom was won primarily by the fact that Picquart did his duty irrespective of prejudice or personal advantage. While we should ignore Polanski’s claim to be another Dreyfus, the message his film brings is one that should challenge every honest person to do the same—and refuse to be complicit in another generation of antisemitic lies.

No comments:

Post a Comment