More than just coups and dictators: Africa's overlooked democratic progress

Despite the recent military coups, the continent also has much to show for when it comes to democratic rights. Israel Hayom spoke with the experts.

David Baron

Israel Hayom

Sep 24, 2023

The clamour for coups among citizens is rising.

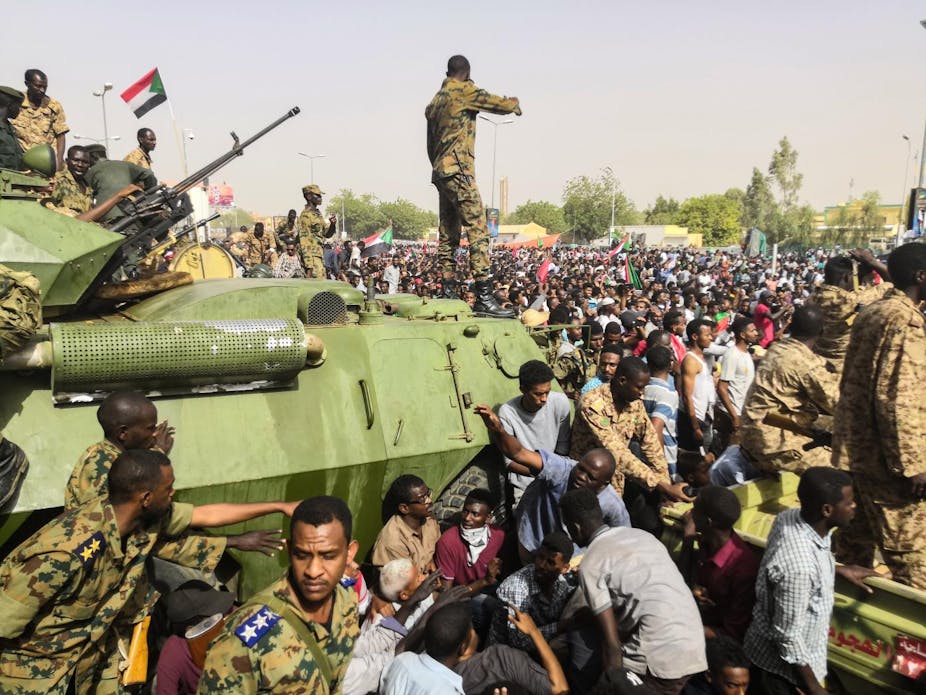

On screen, a group of officers in fatigues appears. One of them sits by the microphone and announces that the serving president has been ousted and that the government agencies have been disbanded or come under its command. Then the military announces that it is taking control due to the failures of the civilian officials or because they have breached the will of the people.

This is, more or less, how a coup in Africa unfolds. Over the past three years, there have been quite a few: Mali, Burkina Faso, and just in the past six months – Niger and Gabon.

Sub-Saharan Africa's image as a region where nothing is stable, except for instability itself, has been reinforced by these developments. It's not just because of coups; it has also become synonymous with dictatorships, with this taking center stage in Israel when groups of Eritrean immigrants who supported and opposed the brutal regime in the African country clashed on the streets of Tel Aviv.

In light of this state of affairs, you could be forgiven for ignoring the fact that the continent has a whole host of stable democracies.

According to the latest report by the think tank Freedom House, out of 54 countries in Africa, only six were considered free as of 2022: Botswana, Cape Verde, Ghana, Mauritius, Namibia, and São Tomé and Príncipe. A few others were on the path to democracy, including Benin, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Nigeria, Senegal, and Zambia

The V-Dem (Varieties of Democracy) report – which uses a host of indices on the scope of democracy in the world as measured by the V-Dem Institute – showed that in Africa there was only one full-fledged (liberal) democracy in 2022 – Seychelles, but electoral democracies like Ghana, Malawi, Senegal, São Tomé and Príncipe were on the verge of being democracies in full.

So what is it that makes it possible for African continents to survive? Israel Hayom spoke with Dr. Joseph Siegle, the director of research at the US-based National Defense University's Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

"I'm reluctant to say that there are universal features among these countries contributing to their relatively better democratic governance performance," Siegle says.

Moreover, all have had their ups and downs," he continues.

"The democratic path is not linear. This is common across the world for low- and middle-income countries prior to consolidating their democratic systems. Even among wealthier established democracies, as we see, these norms can be challenged.

"That said, a couple of governance features bear noting. First, is that most of these countries (with the exception of Ghana and Nigeria) have not had a history of military governments. They've thus been able to avoid the civil-military competition for power and complex transitions away from military governments that 35 African countries have had to navigate. These countries also have a relatively stronger commitment to the rule of law. This has enabled and empowered a shift to constitutionalism and the checks and balances inherent in a democratic system. This has facilitated power-sharing arrangements that have promoted compromises to resolve competing interests. Consistent with the commitment to the rule of law, for the most part, all of these countries have avoided leaders who have tried to evade term limits. In the case of Senegal, and some feared Zambia, if Lungu had remained in power, when leaders did test the term limit rule, they faced strong protests and pushback from citizens. So, parallel to the emergence of these institutions of accountability, these countries have been able to nurture a culture of democratic values among their citizens. As a result of these governance features, these countries have also realized more robust and consistent economic growth and social development than their peers elsewhere on the continent."

Dr. Irit Beck, the head of the African Studies program at Tel Aviv University notes that there is a cluster of democratic states in the southern part of the continent. "This cluster attests perhaps to the degree of post-apartheid South Africa's influence," she says. "South Africa has shown that democracy can work."

Then there is the special case is Senegal. According to Prof. Ruth Ginio from the Department of General History at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, this has more to do with the country's cultural and political heritage.

"During the revolutions of 1848 in Europe, known as the Springtime of Nations, France naturalized the residents of its four oldest colonies in the territory of Senegal," Ginio, whose field of research includes French colonialism in West Africa, says, noting that the French move to grant citizenship to meant that they "could vote for local assembly in Dakar and even send a delegate to the National Assembly in Paris. After France ultimately conquered all of Senegal, millions would be denied rights, but there remained an elite who understood what democracy and a free press are, as well as things that didn't exist in any other African country."

She adds, "I think there has been a lasting influence because democracy is something that you have to learn. Democracy in Senegal has become part of its nationalism, part of its national pride. People are aware of the importance of having their voice heard and that the government cannot act on a whim, as was the case when the current president, Macky Sall, tried to extend his term."

Another feature that makes democracy in Senegal stronger is the separation of religion and state, which can also be traced to the French constitution. Even Islam in Senegal has its proper place. "The Sufi orders, which emphasize the personal connection with God, wield a lot of political influence, and they strongly oppose fundamentalist Islam," Prof. Ginio says. "When they alleged that one of the presidential candidates, Ousmane Sonko, was leaning toward fundamentalism, he quickly issued a vehement denial. As far as the people of Senegal are concerned, Islam should be moderate."

According to the V-Dem indices, Africa was leading the relative number of countries undergoing democratization. Out of 14 such countries in the world, five are in Africa. However, the opposing trend away from democracy, which has been noted in 42 countries worldwide, is shared by 12 African countries. "Africa is different in that democratization processes began relatively late, and this has its impact on how they are perceived," Beck says.

She adds, "South Africa may have become a model, but since the end of apartheid, the same party has been in power, and corruption has tarnished many of the achievements of democracy.

"In Nigeria, there are free elections every four years, but there are also serious security problems due to terrorist organizations in the north and the rampant crime in Lagos. This has had people wonder if democracy has delivered on their expectations. In many cases, the military coups get popular support because of the perception that democracy failed to fulfill its purpose."

But does military rule bring about positive change? "I would say that we have to be careful not to attribute a more altruistic rationale to the military juntas that have seized power in the seven African countries (and counting) since 2020," Dr. Siegle says, adding that "in every case, this was about the military seizing power for power's sake, in every case these countries have had a long legacy of military government."

According to Siegle, "In some instances,

such as Sudan and Chad, the coups were about perpetuating that power.

In other cases, they were about reasserting military authority after a

brief move toward civilian, democratic government (such as Mali, Burkina

Faso, Guinea, and Niger). In Gabon, it was about a highly politicized

military leadership that profited handsomely from the Bongo regime using

the pretext of his unpopularity to take over the vast patronage

networks themselves. Importantly, in the cases of all the democratizers

(Mali, Burkina Faso, Guinea, and Niger), economic and development

indicators were significantly more robust during the period of

democratic government. Therefore, the assertions by the military juntas

in each case that they had to intervene are purely self-serving. That's

not to say that each of these countries didn't have challenges. They

are among some of the poorest in the world. But the relative progress

they had made compared to their periods of military rule is noteworthy.

Similarly, the security environments in both Mali and Burkina Faso, the

locus of violent extremist activity in the Sahel, have accelerated since

the coups. There are twice as many violent extremist events and three

times as many fatalities in these two countries since 2021. So, the

security rationale for the military takeovers is also specious. So,

these coups are about special forces units and presidential guards

seizing power because they can, nothing more."

No comments:

Post a Comment