The war that changed my life – and everyone else's

Fifty years ago, I had been preparing for my Latin exam in university as a 22-year-old who had just completed his compulsory military service a year earlier. But then everyone had their world turned upside down when a nationwide reserve call-up was announced. I was lucky to make it back alive. The dead and the wounded earned the right not to be forgotten.

Amos Regev

Israel Hayom

Sep 24, 2023

In both cases, I felt that I was being targeted by people who had come to kill me but failed. I survived the war, but did I emerge with PTSD? Perhaps all of us – the cohorts of my generation who took part in the battles in the Sinai and the Golan Heights and came back alive – returned with a mental scar. The wailing sirens that disrupted the holiday of Yom Kippur 1973 caught me off guard, like everyone else. I was with my wife at her parents' house in Tel Aviv.

I had been preparing for my Latin exam in university, as part of the history major. But then everyone had their world turned upside down and we all found ourselves at a different kind of test: A war. But what were we to do? It had barely been a year since I was discharged, and I had not been assigned a unit for my reserve service. I was an artillery officer, but only a first lieutenant in the reserves, so apparently the IDF did see any urgency in placing me in the reserves The overall feeling was that Israel's security was in great shape, and there was even talk of shortening the period of mandatory service. But then, against this false sense of calm, the Egyptians crossed the canal and the Syrians breached the defenses; Mt Hermon was taken by the Syrian commando.

I tossed my Latin book to the side because no one could care less about Julius Caesar and his Gallic Wars. My wife and I quickly got back home to Ramat Gan, by foot. Hundreds of people walked and ran just like us. Inside the Kirya base housing the IDF headquarters and the Ministry of Defense, many cars and uniformed officers were moving. This was war after all. I was glued to the radio to hear the latest updates (which were, in fact, false) on what was unfolding on the front, I kept calling the reserves department in the IDF to get an answer about where I should go. It took them a while.

Eventually, they told me to go to the Pilon base near Rosh Pina. But how does one get there? My wife, who wanted to help me get there fast, called Arkia to see if there was a flight from Tel Aviv to the area. "Lady," they responded, "are you out of your mind? There is war. There are no flights." I arrived at the base by bus and with the help of various drivers realized that anyone they see with a backpack must be hitchhiking because they need to get to the front. Upon arriving, I was glad to see several officers from my service. They were busy getting their battalion – the 313rd Battalion – ready (it later got the number 7035).

I joined them and soon realized that I was in great company, with professional and friendly troops who were determined to do the job. The next day we went to the Golan Heights. The war was raging, but we went up to the plateau despite the incoming fire, the shells falling all around us, and smoke billowing everywhere. There were scorched tanks and vehicles. Occasionally, we could see Israeli Air Force jets flying low and then one of the aircraft being downed with a missile. There were also Syrian planes that were intercepted after being chased by our planes.

This was war 24/7, with no respite. And then I saw the Syrian commando helicopter flying north of where we were. But it was clear it was Syrian. There had already been rumors about what the Syrian commando was doing to the troops on Mount Hermon. Later we learned that on that day the Syrian commando carried out a widescale attack and sent helicopters to target the IDF troops in the rear. This included an attempt to conquer Mount Avital and various ambushes on the roads and intersections on the Golan Heights, as well as raids on various IDF units. The choppers were apparently sent to the IDF troops in the central and northern parts of the Golan.

They failed. Most were eliminated, but some ambushed troops from the 7th Armored Brigade's Reconnaissance Company. In this attack, the company commander was killed. He was promoted to captain posthumously.

During my compulsory service, as part of my officers' training, I was sent with one other artillery officer to get complementary training with the Armored Corps because the IDF wanted to replicate such units among artillery forces. This training was a great experience in which I crisscrossed the country to hone my navigation skills and above all – it was of great benefit socially. These were the salt of the earth, the finest men the IDF had, as they say. Several weeks ago, when reading a story on the war in another outlet, I suddenly saw a picture of one of them. His name was Uri; he fought in the war in the 7th Armored Brigade's Reconnaissance Company and was killed.

Seeing his picture brought back memories from that training especially that of Uri. He was one of the stars of the group – professional, easygoing, and smiled a lot. A natural leader. He was killed while fighting against the Syrian commando, along with many others from his unit. Ultimately, after the IDF sent more troops, the Syrians were mostly eliminated in that battle.

After the war, I did a master's degree in military history. A lot has been written on strategy and tactics; on good and bad leaders; on the art of war and how to win; on intelligence and logistics and on heroes and cowards; and on military leaders and ordinary soldiers. But it turns out that in reality, when you are in battle, you need luck first and foremost. I learned this right at the start of my service in the Artillery Corps, during what was later named the War of Attrition with Egypt.

During the 1969-1970 winter, I served as a deputy commander of a self-propelled artillery unit in the 404th battalion. The battalion was deployed along the Suez Canal. This is the first time I learned what counter-battery fire is. This was a dangerous thing. Our battery would get into possession and fire, and then within minutes, someone from the Egyptian side would retaliate with counterfire, with shells landing between our artillery pieces, forcing them to be relocated time and again.

One morning, as we were setting up our pieces, the commander showed up. He brought a new soldier who had just joined the battle. He told me I was in charge of him. I told him, "It's an honor, welcome." We didn't talk any further, we started firing at the Egyptians. The new soldier stood behind the howitzer and helped carry shells and propellant like everyone else. Then we were hit by counter-battery fire. I can't recall where the shells had fallen, but I do remember that the new soldier, who had just arrived that morning, fell on the sand. He had been hit by shrapnel in his head and sustained severe wounds. He died several days later. His name was Shmuel Hadad. He was the first dead soldier I had seen. I would later go on to see more of the war that erupted three years later. Many more. As noted, one needs to be lucky at war. How awful is it that the soldier who arrived that morning, who no one knew, who didn't have a conversation with anyone from the team, was the one killed in that Egyptian attack? Our commander leader, who started running toward us when the attack began, managed to reach us despite shells falling all over us and knocking him down several times.

Three years later, the battalion joined the fighting on the Golan Heights. As we made our way, we saw scorched IDF tanks, and burned bodies of IDF troops – and the same for the Syrians. We fired heavily on the Syrians as we made our way, as well as on the Iraqi and Jordanian reinforcements. We heard on the radio that we had made "good hits". We fired so much that the barrels were so hot we could not touch them. We kept running out of ammunition really fast, and in one case, when a truck arrived to replenish our supplies, we took the shells directly to the barrel.

Eventually, the Syrians were repelled back. What next? The battalion made it to the Quneitra. We knew that the IDF planned to go into a counter-offensive. We found ourselves spearheading this, just next to the tanks. People often think that artillery stays at the rear, firing shells to hit some targets 10 miles away, while the tanks and infantry are fighting in forward positions. This is not true. Especially not for us. Our mortars had a short range and they were considered to be auxiliary to the armored units.

We were side by side with the tanks, and despite all the chaos, we found some time to talk – about the shock of how the Arabs caught us off guard on both fronts We didn't have real-time data but we wanted to know how this could happen. Where was the intelligence? Where was the government? Where were all the national security figures? How is it that the IDF, who only six years earlier, crushed all the Arab armies, found itself against an Egyptian force that took virtually all the eastern bank of the Suez Canal and repelled our counterattack? How come the Syrians made it almost all the way to Tiberias? How is it that people were talking about the end of the "Third Jewish Commonwealth? "All this was a shock, but above all, it was insulting. It meant that something was not right and that we were paying for that. Our battalion was relatively lucky, as we only had one fatality during the war and about 14 wounded.

Other units were wiped out, including my friend Ofer Neeman, whose battery came under heavy fire at the start of the war from Egyptian Katyushas that hit ammunition vehicles and killed many.

His good friend, Danny, was also from our course. He was severely wounded when he tried to help the casualties and later succumbed to his wounds. He was given the rank of captain posthumously. Another friend, Ilan, was a howitzer battery commander. One of the batteries – not his – was bombarded from the air and soldiers died. The picture of the aftermath, with the damaged 175 mm guns later became one of the iconic images of the war. Ilan and his battery crossed the canal as well under heavy fire.

One of his men was killed; others were wounded. We generally had counter-battery fire and various incidents with MiGs. When we were stationed near Quneitra, we got heavy fire that hit us right within the battery's premises. In one incident, the shrapnel almost killed us but we ducked on time. I had on my hand an Omega Speedmaster that I had received a year earlier as a present. My officer realized what I was wearing, and with his gallows humor said, "Just remember that if something happens to you, I get the watch."

I have not taken that watch off ever since. It is 52 years old. It is manually winded and it still works. Then, in the morning before the attack into Syria, we were hit by MiGs. Unlike the commando helicopter I saw from far away, these MiGs were very close. They flew right in front of us and then turned our way and divebombed us. It was scary – that was the scariest thing. It was a scene taken right out of World War II, as if I was targeted by Stuka bombers, with sirens blasting.

During that raid, one of our soldiers died. During the bombardment, I took cover under a boulder. I just glued myself to the ground and told myself that if I somehow made it back alive, I would have a child. It was just unthinkable, I thought to myself during those moments that will forever be seared in my memory, that I will end my presence in this world at the age of 22. Having grown up on the stories of my uncle – one of the fighters in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising who fought with bravery to his death, I was not going to let some random Syrian bomber take me out.

I was lucky. I wasn't killed. That's how my eldest was born. From what I heard after the war, my comrades had the same experience, as well as many other soldiers. That is how the term "the children of the winter of 1973" was coined. Our children were those born in the fall of 1974.

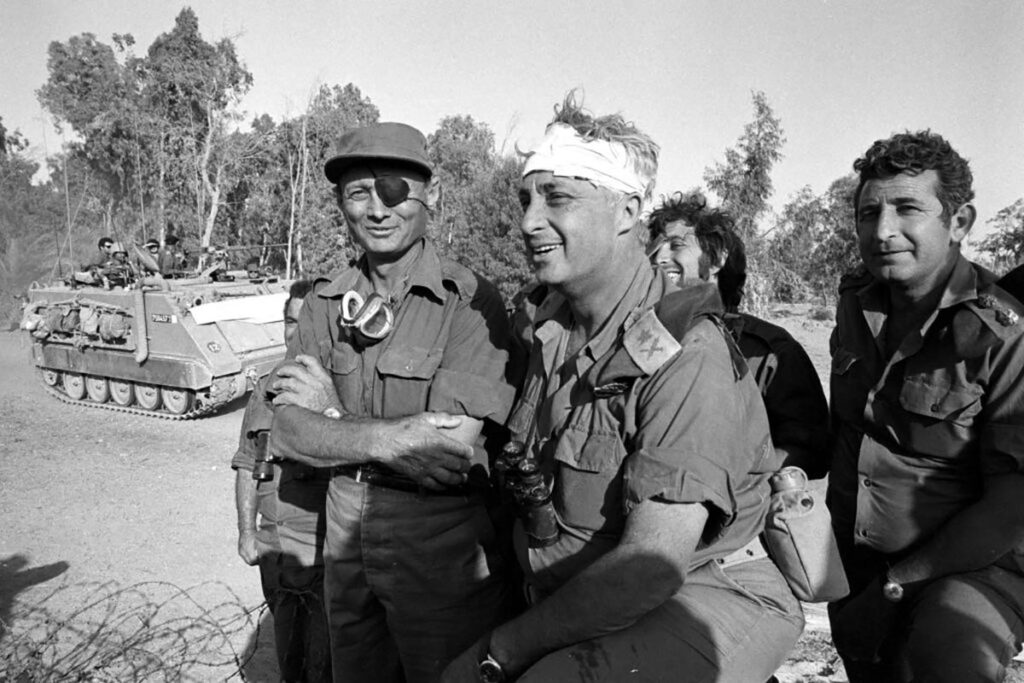

Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir, right, and Defence Minister Moshe

Dayan meet their troops on October 21, 1973, on the Golan Heights during

the Yom Kippur War

Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir, right, and Defence Minister Moshe

Dayan meet their troops on October 21, 1973, on the Golan Heights during

the Yom Kippur War

The battalion eventually advanced well into Syrian territory under heavy fire. In one case, we found ourselves on the highway to Damascus ahead of everyone else: An artillery battalion of heavy mortars that looked like shoe boxes had suddenly become the spearhead of the Israeli onslaught.

From the right, we had incoming Syrian fire. From the left, Israeli fire. In the interludes, we – the officers and the commanders – went to the narrow road on the side and instructed the artillery pieces to turn in various directions using the agreed-upon hand gestures. We eventually made it out of the area safely, but one Syrian unit spotted us and came for us with counter-battery fire. First with artillery rounds, then with Katyushas. I already said that we were lucky. We somehow survived and made it all the way to Syrian villages on the foothills of Mount Hermon. We fired a lot of rounds to help the infantry reconquer the mountain.

And then the ceasefire took effect and the war ended. We were comforted by the fact that we had passed through the deserted positions of the Moroccan auxiliary force that had come to help the Syrians. The troops had left behind great food from abroad: sardines, canned goods, and La Vache qui Rit cheese. We didn't know that this was not the end of our deployment – we stayed in the reserve call-up for another four months straight then went on leave for a month only to be redeployed for another two months. We didn't know that we would have to endure one of the coldest winters, with the artillery being covered with snow.

The continued deployment gave us more time to figure out what had happened. We didn't know that there would be an attrition war with the Syrians just after the war ended. We didn't know that we would have to spend Passover Eve on high alert because someone assessed that the Syrians might resume hostilities. They didn't, but by that time the true casualty figures had emerged: more than 2600 Israeli dead. We already knew who among our friends died, and who was wounded. Practically every street had a resident who had been killed or maimed. We knew that militarily Israel had won: The IDF had reached the 101st km from Cairo; the IDF's artillery had advanced to the point that its guns could threaten Damascus. We won, but the pain was unbearable. What had just happened? w

There was little credible information to rely on. Rumors were circulating about Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, Prime Minister Golda Meir, about IDF Chief of Staff David Elazar, and the head of the IDF Military Intelligence Directorate Eli Zeira. Just after the war, the book "The Shortcoming" came out, written by several journalists. It was a big hit, as it was the first time that an answer had been given. The Hebrew title for the book – "Mehdal" – suddenly became an official word that everyone knew; part of our collective historical lexicon. And then the Agranat Commission investigated the war. While its findings were addressed at the military echelon, it also sealed the fate of Meir and Dayan's term in office, and the government resigned. It took another three years before Israelis decided to punish the Left with the 1977 electoral upset that brought Menachem Begin to power.

There were many reasons for the Right's rise, but the war was the main one. Israeli voters had realized that they could no longer trust anyone, except the fighters. As the years went by, more information came to light; the minutes from the meetings were published and even the picture of the spy that Israel had within Egyptian ranks had become known. All this makes the anger even greater. How could the leaders ignore the obvious signs? How come they were so wedded to their paradigm and had us forsaken?

While the conduct during the actual fighting was better, the actual shortcomings of the leadership before the war could not be forgiven, even as more information came to light on the "mehdal." The passage of time only shows how much worse it was than originally thought. What does all this tell us 50 years later? Somehow, during my military service, I discovered Mahler's symphonies. I went to war with Mahler's Symphony No. 2, known as "The Resurrection Symphony." it takes time for a young man to realize that despite Judgement Day being a key theme of that piece, its ending is a good omen: after Judgment Day, people come to life with a big victory. Yes, it was tough, and perhaps a bit cliche. But we proved ourselves.

Israel was attacked and it appeared to be on the verge of annihilation. We went to war to fight for our lives, our families, our wives, our children, and our friends. We heard the song Lu Yehi (Naomi Shemer's "Let it be") and we wished for the best. So, what did we have? I have written on the war and my experience over the years. Some of what I wrote here has already been published in previous anniversaries. I didn't think I had much more to write, but 50 years is indeed a big milestone. The war changed everyone's lives. It will stay with us. Al l the IDF troops, in all the wars and operations and routine security duty should be honored. But what should the Yom Kippur War get?

In the US, I have noticed a common tradition. When people see someone in uniform or with a shirt saying "veteran," they extend their hand and tell them "Thank you for your service." He usually responds, "Thank you for your support." This is mostly what I think the Yom Kippur veterans deserve, on top of the support for the bereaved families, the injured, and those suffering from PTSD. They earned the right not to be forgotten; even after 50 years we must not forget to say one word to those who were there: "Thank you."

No comments:

Post a Comment