New D.A. Data Reveals Systemic Failures In Murder Prosecutions

Houston Watch

July 27, 2023

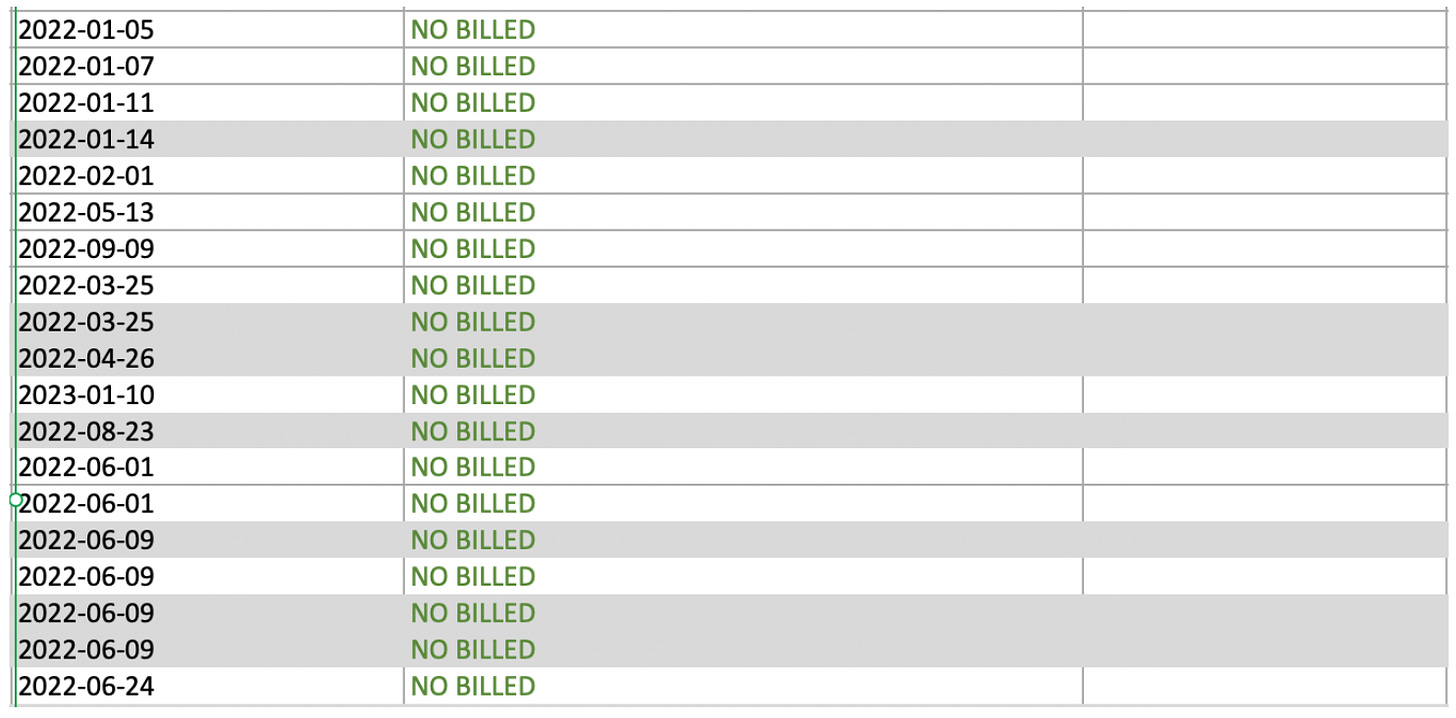

From January 2022 through June 2023—a period of eighteen months—Harris County has endured nearly 700 murders. Over the same time period, the District Attorney’s Office only managed to secure murder convictions in ten of those cases, according to data provided to Houston Watch by the District Attorney’s Office pursuant to a public records request.

In four additional cases, the D.A.'s originally filed a murder prosecution, but ultimately were forced to plead, or chose to plead, the case down to manslaughter (three cases) or injury to a child (one case).

For example, the District Attorney’s Office charged a man with murder after he shot to death a sixteen year old boy. This man was already out on bail awaiting trial for aggravated assault causing serious bodily injury against a family member when he killed the teenager and—in a separate case—committed another felony assault involving “punching and stomping on” a man’s face and body.

Finally, after the man killed the teenager, prosecutors asked the trial court to lock the defendant in jail until the murder trial because they believed him to be so dangerous that he could not be trusted to be in the community. Yet, the murder trial never happened. Instead, the prosecution could only secure a manslaughter conviction carrying a three year sentence.

Unfortunately, that’s not the only example of Ogg’s prosecutors offering a plea deal and a lenient sentence in a murder case. For example, in one recent case, a man with separate prior convictions for burglary and aggravated robbery negotiated a four year sentence despite killing a person by kicking him, punching him, and hitting him with a brick.

In a third murder case that the prosecution reduced to manslaughter, the defendant received just eight years in prison. Normally, with a murder conviction—as opposed to a manslaughter plea deal—the defendant would receive a life (or decades-long) sentence. It seemed like a slam dunk case, too. For example, toll booth cameras placed the defendant’s car near the scene of the murder, and an eyewitness picked the defendant out of a line-up, told police officers that she saw the defendant waive a black handgun at a car that cut-off his car, and then she watched him shoot the victim to death.

Consider, for example, despite the adage that a grand jury will indict a ham sandwich, Harris County grand juries refused to indict 19 of the murder charges that Ogg’s prosecutors brought before them. Either Ogg’s office is botching the easiest part of the trial process, or else utterly failing to screen weak cases—including people who might be innocent. Neither scenario reflects kindly on Ogg’s leadership.

Ogg’s prosecutors also had to dismiss another dozen—or 26%—of the murder prosecutions. That means that Ogg’s team withdrew the charges without securing a murder conviction. For example, in one case in which prosecutors dismissed the charges, an eyewitness told police officers that she witnessed the defendant shoot four people—one who died— in a nightclub. The witness picked the defendant out of a lineup. Moreover, the defendant, who owns a “Glock … with a device that converts a semi-automatic handgun to a fully automatic handgun,” was also caught on video running away from the club and handing a black gun to another male. Again, it’s a slam dunk set of facts that most prosecutors would turn into a murder guilty verdict, but Ogg’s prosecutors dismissed it.

High profile and catastrophic failures to secure murder convictions are not new for Ogg’s office. Indeed, over a two week period spanning the end of June through early July of this year, the Harris County District Attorney’s Office failed to secure a conviction at trial in six different murder cases. Then, last week, prosecutors lost another four murder cases—two not guilty verdicts and two dismissals at trial.

What’s going on here?

The most likely explanation, local lawyers tell Houston Watch, is a combination of inexperienced prosecutors and chronic lack of prioritization, both of which have contributed to a workplace that prosecutors have called “bad”, “toxic,” “hostile” and “mismanaged beyond comprehension.”

These same prosecutors point the finger at Ogg and her top leadership, calling them “horrible”, accusing them of displaying “staggering incompetence,” and blaming them for “this place [having] the worst work environment ever, and cater[ing] to the incompetent and lazy.”

An independent research firm called PFM Consulting Group came to similar conclusions in a study that the Harris County Commissioners Court commissioned. The researchers concluded that Ogg’s system for case management—in short, how Ogg prioritizes and processes cases—as “inherently inefficient” to the point where prosecutors simply “do not feel responsible for working up the case, tracking down discovery, and ensuring that it moves forward.” Due to these chronic problems, the chiefs who run the various divisions within the office told the researchers that “attorneys burn out quickly and resign,” which leads to a staff composed of “inexperienced prosecutors [who] lack the knowledge and insight that comes from prosecuting cases.”

The toxic brew of low morale, inexperienced prosecutors, and poor prioritization renders it extremely difficult to secure convictions in serious, complicated cases such as murders. Take, for example, a recent murder case that Ogg’s office lost which Houston Watched reported on earlier this month, involving a three year-old boy who died from : “multiple blunt force injuries” in a case where the coroner detailed “100 scars of the head, neck, chest, abdomen, back and all extremities” indicating “chronic abuse.”

Pasadena police officers arrested the boy’s stepfather; the Harris County District Attorney’s Office launched a homicide prosecution; and the grand jury returned a murder indictment. Here’s how Houston Watch described the results on the prosecution:

Days before trial, again over five years after the boy died, the prosecution asked the judge to delay the proceedings. In its motion opposing the delay, the defense shed light on what appears to be deep incompetence on behalf of Ogg’s prosecutors. Specifically, the defense accused Ogg’s prosecutors of a “lack of diligence” that stretches “all the way back to the inception of the charge [5 years prior]”.

To give a few examples of the “lack of diligence” from Ogg’s prosecutors, the defense noted that “the State violated this court’s discovery order … by failing to file a subpoena .. at least 14 days or more prior to trial” and cannot show this court that it did anything to communicate this agreed reset to its witnesses. [Moreover,] more than 120 days have elapsed where alternative dates could have been procured before schedules in later 2023 solidified. Again, there is no showing that any of this was done.”

In other words, it appears the prosecutors couldn’t secure a conviction because Ogg’s prosecutors could not—or could not be bothered to—take basic steps to ensure that their most important witnesses knew the trial date and showed up to court on the right day. In any given case, it is possible to make excuses—or extend the grace that all people deserve when they botch a difficult job—but as Ogg’s own data reveals the office’s track-record in murder prosecutions filed since January 2022 is abysmal, and over the past 30 days a dire situation is becoming rapidly more catastrophic as the losses in murder cases continue to mount.

1 comment:

So, what's new? Harris County is a nest of shady politicians who hire bureaucratic snakes and yet they continue to be elected by the citizens.

Post a Comment