Trey Rusk wrote:

First let me say that I worked at the Texas Department of Corrections for W.J. Estelle for one year in 1974. I was the top pistol shot in training.

I married my wife just after gaining employment and we lived in Huntsville.

TDC was a dismal place with little budget for healthcare and inmates routinely died due to a lack of basic services. Inmates were punished by guards who wrote them to attend a court of guards overseen by a higher-ranking guard. Solitary was used frequently.

TDC was not a place you wanted to be as an inmate or employee. It was the worst job I ever had, bar none. I began looking for another job shortly after being hired.

Just about the only bright spot of working there was attending the Prison Rodeo. Below is a story about that event.

_________________

Texas Prison Rodeo

By: Sylvia Whitman

Texas State Historical Association

January 24, 2020

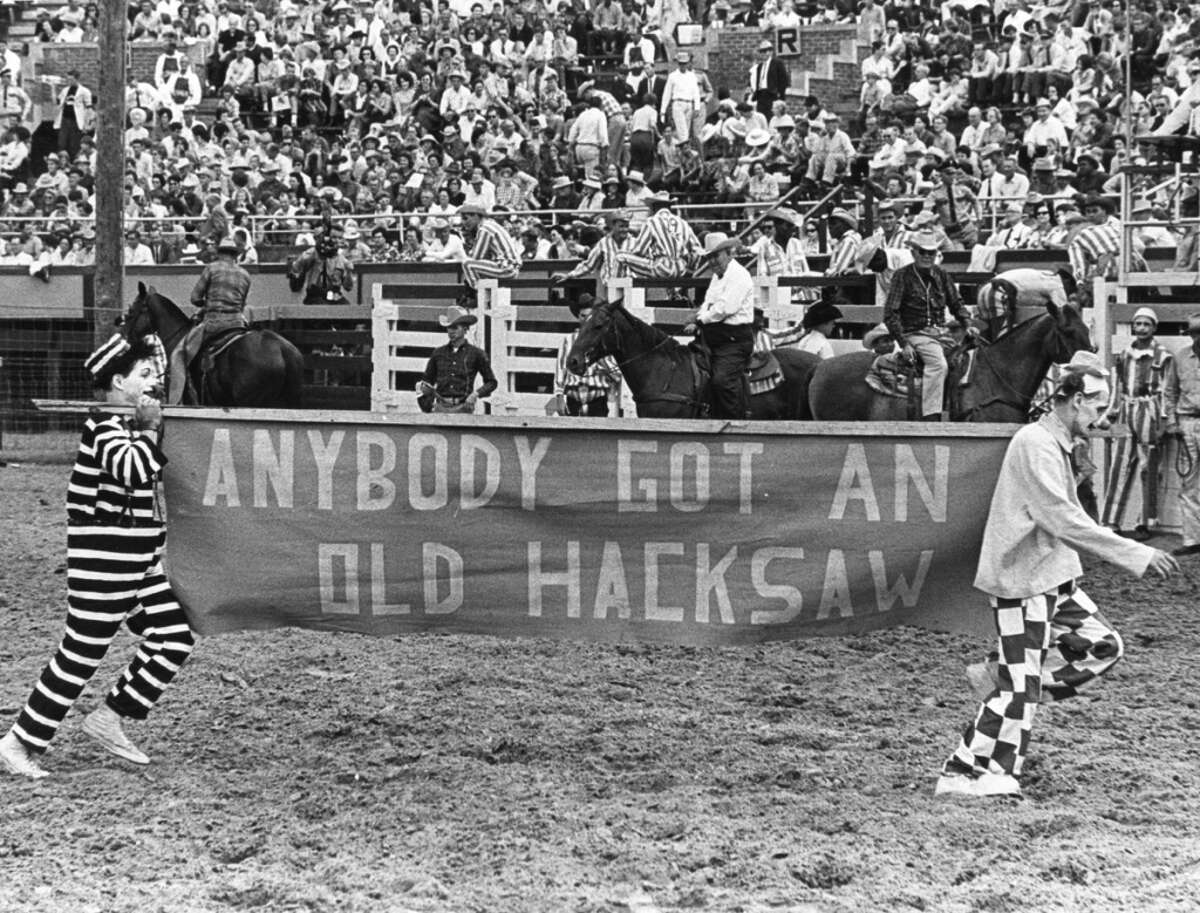

This undated photo shows inmates in the Texas Prison Rodeo participating in a 'mad cow scramble.'

The Texas Prison Rodeo, instituted in 1931 by general prison manager Marshall Lee Simmons as recreation for inmates and entertainment for staff and their families, soon earned a reputation as the wildest of cowboy shows, attracting huge crowds and favorable publicity to the Huntsville unit. After securing the blessing of local clergy to hold the rodeo on Sunday afternoons in October, Simmons trucked in livestock, participants, and spectators from the outlying prison farms to a vacant field behind "The Walls." Within two years public attendance swelled from a handful of outsiders to almost 15,000, prompting prison officials to erect wooden stands and charge admission. The revenue raised covered costs and subsidized an education and recreation fund that provided perquisites from textbooks and dentures to Christmas turkeys. In 1986, just before structural problems with the stadium suspended the rodeo indefinitely, it grossed $450,000 from an estimated 50,000 fans. The Texas Prison Rodeo provided the usual rodeo events, calf roping, bronc riding, bull riding, bareback basketball, and wild cow milking. In the "Mad Scramble" ten surly Brahmans charged out of the chutes simultaneously, snorting and bucking as the inmates in the saddles tried to race them to the other side of the arena. In "Hard Money" red-shirted convicts vied against the clock and each other to snatch a tobacco sack full of cash from between the horns of a bull. By 1933 rodeo directors had banned steer wrestling, apparently because they feared the event posed a greater injury risk than other events. At first Simmons limited participation to experienced ranch hands, but by the 1940s any male inmate with guts and a clean record for the year could compete at open tryouts in September for one of 100 or so rodeo slots. Until their transfer from the Goree unit to distant Gatesville in 1981, women also entertained and participated in calf roping, barrel racing, and greased pig sacking.

Prisoners earned money for performing-two dollars in 1933, ten dollars in 1986-and for winning. Supplemented by the crowd, the "Hard Money" sometimes totaled as much as $1,000 in the 1980s. Yet for many convicts the purses mattered less than the pride of accomplishment. Sentenced to life imprisonment for the axe murder of his father, O'Neal Browning gained celebrity on both sides of the bars as the top hand in seven rodeos over three decades. Clowns amused the crowd and distracted the bulls while downed riders made a getaway. By popular demand, 1939 rodeo clowns Charlie Jones and Louie Nettles-"Fathead" and "Soupbone"-broadcast their routines on Huntsville's weekly radio program, Behind the Walls. "They give me life fer just goin' off an leavin' my wife." "Now wait a minute, Fathead...How did you leave your wife?" "Why, I left her dead!" With equally irreverent humor the announcer paced the rodeo, commenting on the ups and downs of each inmate. "He's going to be plenty good some of these days. He's eligible for ninety-seven more of these affairs." During halftime western and country music stars such as Tom Mix, Loretta Lynn, and Willie Nelson performed for the audience. At the end of the afternoon a panel of judges awarded a silver belt buckle to the best all-around competitor.

The logistics of the rodeo involved the entire prison system, as well as the local community. Farm inmates helped round up wild steers from river bottom pastures. At the Goree unit women sewed the cowboys' zebra-striped uniforms. Printers and journalists from "The Walls" produced souvenir programs, and leatherworkers tooled saddles and chaps for riders whose families could not provide equipment. On rodeo weekends Huntsville residents capitalized on the influx of tourists by opening their restaurants, stores, and driveways. Prison guards also worked overtime, supervising the "rolling jails" of convict spectators from the farms and "the midway" of inmate arts and crafts and music. Like the men in the saddle, the Texas Prison Rodeo tumbled from time to time. Despite the medical personnel standing by, two inmates died in the arena. Others suffered broken bones and assorted injuries. One year a pair of prisoners escaped by slipping under the bleachers, where an accomplice had left civilian clothes. As they exited, a guard spotted them "and-thinking that they were sneaking in-promptly threw them out." By the 1950s, as rodeo professionals staged exhibitions and big-name entertainers edged out the inmate string bands and gospel choirs, a few fans pined for the cozier contests of the early years. But the popularity of the rodeo always outstripped the facilities. In 1938 the warden at Huntsville doubled the seating after turning away many tourists the year before. Although war cutbacks cancelled the show in 1943, the Victory Rodeo of the next year lured back such a following that officials replaced the wooden bleachers with a concrete-and-steel structure in 1950. While the construction was underway the show was moved to Dallas. Over the next decade annual attendance peaked at about 100,000, but by the 1970s and 1980s the energy crisis, bad weather, and lack of advertising had decimated the crowd. Still, the rodeo was drawing tens of thousands of supporters when engineers condemned the stadium at the end of 1986. Unable to raise half a million dollars for renovations, prison officials ended the proud tradition of "outlaw meets outlaw" in the dusty ring behind "The Walls." In the early 1990s attempts to revive the rodeo were unsuccessful.

No comments:

Post a Comment