In breakthrough, Bar-Ilan University scientists form artificial lab-grown testicles

Creation of male gonad organoids using mice could lead to similar work using human tissues that could support advancements in infertility treatments

Dr. Nitzan Gonen leads a team of researchers that have created testicles in a laboratory at Bar-Ilan University in Ramat Gan, Israel

In a scientific first, researchers at Bar-Ilan University have created testicles in a laboratory — a discovery that they hope could lead to a better understanding of sex determination as well as advances in infertility treatment.

The “laboratory testicles” are not life-size, but are organoids, which are miniature and simplified three-dimensional versions produced in vitro that mimic the key biological functions and structures of an organ.

The new achievement was recently published as a peer-reviewed study in the International Journal of Biological Studies.

“This latest study comes out of my lab’s focus on the process of sex determination and the development of the gonads, which are testes in males and ovaries in females. We have been looking into disorders of sex development [formerly referred to as intersex], which occur in 1 in 4,000 births,” said principal investigator Dr. Nitzan Gonen.

Until now, there was no choice other than to study sex determination in vivo, mainly using mice. This is a long and complex process that involves genome editing, producing mice with genetic mutations, and then opening them up at a certain point in their development to examine their gonads.

“So to better understand disorders of sex development and how the gonads develop and function in general, we knew it would be extremely helpful for us to have an in vitro system in the lab. We wanted to have a model of the testes in a dish that would have a lot of cells that we could insert mutations into and harvest cells from for all kinds of experiments,” Gonen said.

Whereas significant progress has already been made by scientists in developing female reproductive organoids, so far there are no parallel breakthroughs for testes, which are responsible for producing sperm and male sex hormones like testosterone.

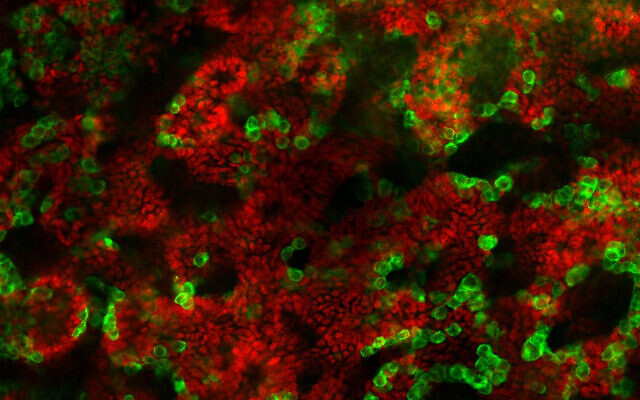

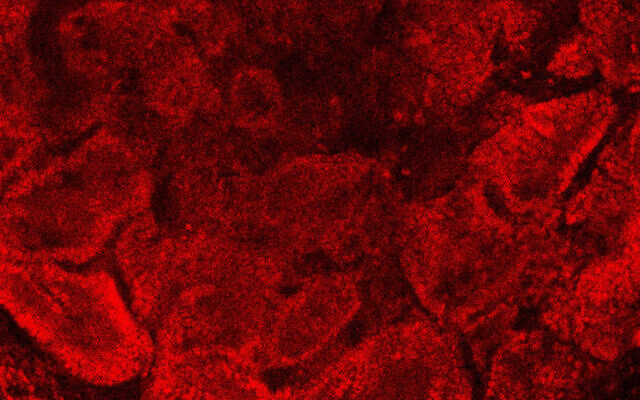

Therefore, the goal was to create an organoid with the three types of cells found in the testes. The first are germ cells, which give rise to sperm. The others are Sertoli cells, which nurture the germ cells so they can produce sperm, and Leydig cells, which secrete testosterone.

Initially, Gonen and her team took embryonic stem cells and succeeded in turning them into early-stage testes cells through a process called regenerative biology. However, there was a glitch.

“It hit me that if I took these really early gonadal cells and put them in a standard dish with basic media, I would not be able to maintain them. So this approach of generating the gonadal cells from stem cells would not help me,” Gonen said.

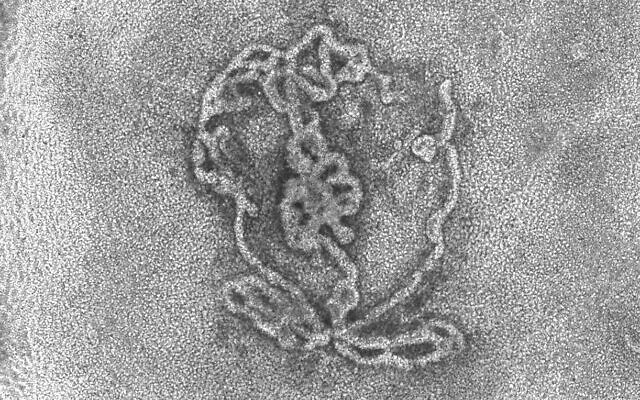

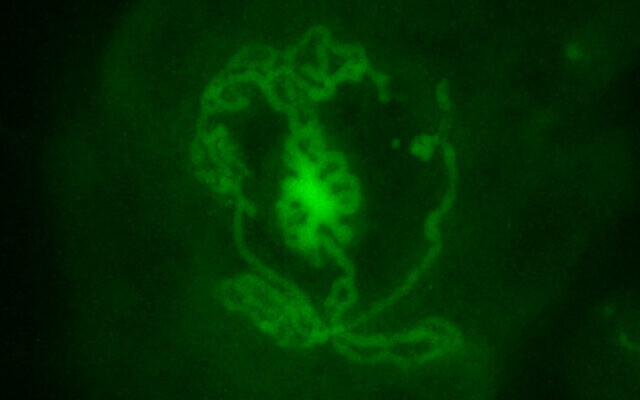

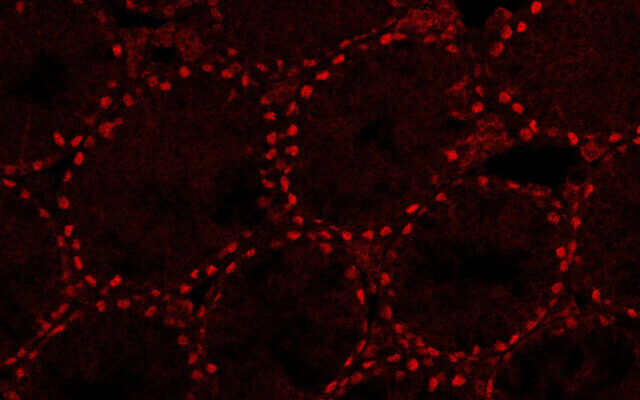

The next step, which was the focus of the newly published study, was to take testes of three to four-day-old mice pups and disassociate them into single cells. Through a trial-and-error process of using different techniques, Gonen and her team succeeded in growing these into testes organoids replete with the proper structures of germ cells, Sertoli cells and Leydig cells.

They found that the younger the pups were, the better their cells were able to be grown into “laboratory testes.”

“We were able to preserve these for a period of nine weeks, which is a long time and something that no one has been able to do before,” Gonen stated.

“We checked the expression of all the different markers of the cells during those nine weeks and we saw that they were very similar to how things are expressed in real testes,” she said.

According to Gonen, this nine-week period is theoretically long enough for the testes to begin spermatogenesis (the creation of sperm). She said she saw initial signs of this, but further study needs to be done to be sure that this is occurring.

“Theoretically, the process of spermatogenesis should take 34 days in mice. So maybe there are cells inside that that have already done that and we just don’t know yet. We are working on that now,” Gonen stated.

Gonen shared that she is eager to move the research forward from mice to humans so that issues of infertility can be addressed.

In one possible application, she noted, some boys have cancer and must undergo chemotherapy treatments that destroy the stem cells in the testes that develop into sperm at puberty.

In Israel and other countries, such a pre-pubescent boy and his parents are given the option of the boy undergoing a laparoscopic procedure to extract a testicular tissue biopsy. This biopsy is divided into slices and frozen. However, at this point, there is nothing that can be done to generate sperm from those cells.

In an attempt to help these children eventually be able to biologically father children, Gonen is working with a physician at Hadassah Medical Center who is providing her lab with some slices of these frozen samples.

“We will try to do more or less the same with these boys’ gonadal cells as we did with the mice pups’ cells. We will dissociate the testes cells and rebuild them back to see whether we can generate human testes organoids that function like they should in terms of producing sperm,” Gonen said.

She also wants to see if she can help adult men with infertility, noting however that a different approach would be needed since she was only successful in creating “laboratory testes” from mouse pups and prenatal mice. When her team tried the approach on older mice it didn’t work because of changes that the testes go through during puberty.

Gonen thinks the solution may be to take somatic cells, such as skin cells, from adult men and revert them into induced pluripotent stem cells and grow those.

“The hope would be that the resultant testes organoids would be

hardier and survive longer than the ones grown from embryonic stem cells

and that they would produce sperm for in vitro fertilization of a human

egg,” she said.

No comments:

Post a Comment