Iran signals a major boost in nuclear program at key site

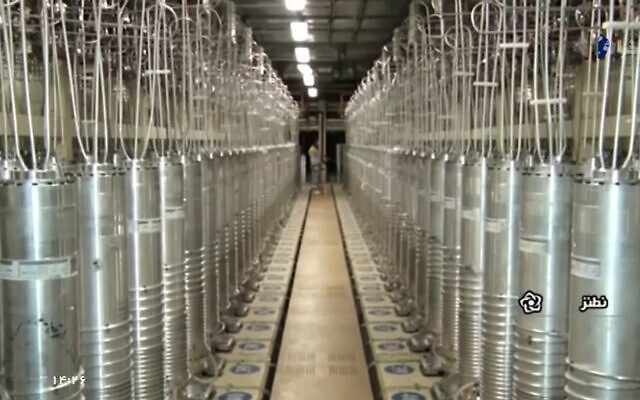

Hundreds of new centrifuges would triple Iran’s uranium enrichment capacity at a deeply buried underground nuclear facility.

Inspectors with the International Atomic Energy Agency confirmed new construction activity inside the Fordow enrichment plant, just days after Tehran formally notified the nuclear watchdog of plans for a substantial upgrade at the underground facility built inside a mountain in north-central Iran.

Iran also disclosed plans for expanding production at its main enrichment plant near the city of Natanz. Both moves are certain to escalate tensions with Western governments and spur fears that Tehran is moving briskly toward becoming a threshold nuclear power, capable of making nuclear bombs rapidly if its leaders decide to do so.

At Fordow alone, the expansion could allow Iran to accumulate several bombs’ worth of nuclear fuel every month, according to a technical analysis provided to The Washington Post. Though it is the smaller of Iran’s two uranium enrichment facilities, Fordow is regarded as particularly significant because its subterranean setting makes it nearly invulnerable to airstrikes.

It also is symbolically important because Fordow had ceased making enriched uranium entirely under the terms of the landmark 2015 Iran nuclear agreement. Iran resumed making the nuclear fuel there shortly after the Trump administration unilaterally withdrew from the accord in 2018.

Iran already possesses a stockpile of about 300 pounds of highly enriched uranium that could be further refined into weapons-grade fuel for nuclear bombs within weeks, or perhaps days, U.S. intelligence officials say. Iran also is believed to have accumulated most of the technical know-how for a simple nuclear device, although it would probably take another two years to build a nuclear warhead that could be fitted onto a missile, according to intelligence officials and weapons experts.

Iran says it has no plans to make nuclear weapons. But in a striking shift, leaders of the country’s nuclear energy program have begun asserting publicly that their scientists now possess all the components and skills for nuclear bombs and could build one quickly if so ordered. In the past two years, Fordow has begun stockpiling a kind of highly enriched uranium that is close to weapons-grade, with a purity far higher than the low-enriched fuel commonly used in nuclear power plants.

While Iran’s stockpile of enriched uranium has been growing steadily since 2018, the planned expansion, if fully completed, would represent a leap in Iran’s capacity for producing the fissile fuel used in both nuclear power plants and — with additional refining — nuclear weapons.

In private messages to the IAEA early last week, Iran’s atomic energy organization said Fordow was being outfitted with nearly 1,400 new centrifuges, machines used to make enriched uranium, according to two European diplomats briefed on the reports. The new equipment, made in Iran and networked together in eight assemblies known as cascades, was to be installed within four weeks. A leaked draft of the Iranian plan was initially reported by Reuters.

The Biden administration reacted to Iran’s planned expansion with a warning.

“Iran aims to continue expanding its nuclear program in ways that have no credible peaceful purpose,” State Department spokesman Matthew Miller said Thursday. “These planned actions further undermine Iran’s claims to the contrary. If Iran implements these plans, we will respond accordingly.”

While the IAEA has been aware of Iran’s plans to increase its production of enriched uranium, the size of the planned boost took many analysts by surprise. If fully executed, the expansion at Fordow would double the number of working centrifuges at the underground facility, within a compressed timeline of about a month. A proportionally smaller, but still substantial, increase is on track at Natanz.

According to diplomats with access to confidential IAEA documents, Iran’s expansion plan also calls for installing equipment that is far more capable that the machines that now make most of Iran’s enriched uranium. At Fordow, only newer-model machines, known as IR-6s, were to be installed, reports show, a substantial upgrade from the IR-1 centrifuges currently in use there.

The 1,400 advanced machines would increase Fordow’s capacity by 360 percent, according to a technical analysis provided to The Post by David Albright, a nuclear weapons expert and president of the Institute for Science and International Security, a Washington nonprofit.

Within a month after becoming fully operational, Fordow’s IR-6s could generate about 320 pounds of weapons-grade uranium, Albright said. Using conservative calculations, that’s enough for five nuclear bombs. In two months, the total stockpile could climb to nearly 500 pounds, Albright added.

“Iran would achieve a capability to breakout quickly, in a deeply buried facility, a capability it has never had before,” Albright wrote in an email.

Iran’s expansion plans for the Natanz plant call for adding thousands of centrifuge machines of a different type, known as the IR-2M. Albright calculated that Natanz’s overall production capacity would increase by 35 percent.

Since the U.S. withdrawal from the nuclear deal, Iran has restricted IAEA inspectors’ ability to monitor the country’s production of advanced centrifuges. But agency inspectors in their visit to Fordow last Tuesday saw technicians beginning the installation of the IR-6 machines, according to a confidential summary shared with IAEA member states.

“It is totally credible,” Albright said of Iran’s expansion plans. “We have no idea what they’ve been doing with centrifuges. We’ll know their capability fully only after they’ve installed the machines.”

Iran chose to disclose its plans after IAEA member states approved a formal reprimand on June 5 criticizing Iran for its nuclear defiance. The IAEA Board of Governors resolution cited the “continued failure by Iran to provide the necessary, full and unambiguous co-operation” with the IAEA’s oversight teams. Iranian officials promptly fired back, with one adviser to Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, vowing in a social media post that Tehran “won’t bow to pressure.”

A spokesman for Iran’s permanent mission to the United Nations said Tehran had strictly followed the rules for notifying the nuclear watchdog of its plans. The spokesman confirmed that the decision to do so was directly linked to the June 5 censure by IAEA members states.

“In this instance, in response to the Board of Governors’ unnecessary, unwise, and hasty resolution, Iran has officially communicated its decision to the IAEA,” the spokesman said in an email.

While the 2015 nuclear accord is still technically in effect, Iran has systematically flouted each of its major provisions in the years since the Trump administration walked away from the deal. The accord was negotiated during Barack Obama’s presidency by the United States and five other world powers, plus the European Union, and known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA.

The agreement was condemned by the Israeli government and panned by many members of Congress, both Republicans and Democrats, because of its perceived shortcomings — particularly its “sunset” provisions that allowed several key restrictions to expire in 2031, just 15 years after the pact went into effect. Yet, until 2018, Iran was seen to be largely complying with the accord, which sharply restricted its ability to make or stockpile enriched uranium in return for sanctions relief.

Iran has shown little interest in reviving or improving the accord since 2018. The Biden White House, after a flurry of activity to restart negotiations in the administration’s early months, has largely abandoned the project, focusing instead on a strategy of military strikes against Iran-backed militias combined with quiet diplomacy aimed at keeping Iran from crossing nuclear red lines.

Despite its increasingly provocative behavior, Iran for now appears unwilling to risk a U.S. or Israeli military strike by actually building and testing a nuclear weapon, U.S. analysts say.

“We do not see indications that Iran is currently undertaking the key activities that would be necessary to produce a testable nuclear device. And we don’t believe that the Supreme Leader has yet made a decision to resume the weaponization program that we judge Iran suspended or stopped at the end of 2003,” said a U.S. official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity under rules set by the administration for discussing the matter. “That said, we remain deeply concerned with Iran’s nuclear activities and will continue to vigilantly monitor them.”

Tehran’s efforts to portray itself as a threshold nuclear power allows Iran a measure of ambiguity that suits Tehran’s purposes, said Robert Litwak, the author of several books on Iran’s nuclear weapons proliferation and a senior vice president at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, a Washington think tank.

“Iran’s nuclear program is both a deterrent and a bargaining chip,” Litwak said. While its planned expansion is more evidence of “pushing the bounds,” such moves simultaneously strengthen Tehran’s hand, should the regime decide that a return to the negotiating table serves its interests, he said.

“Iran’s nuclear intentions should be viewed through the prism of regime survival,” Litwak said. For now, at least, “Iran does not face an existential threat that would compel the regime to cross the line of overt weaponization.”

No comments:

Post a Comment