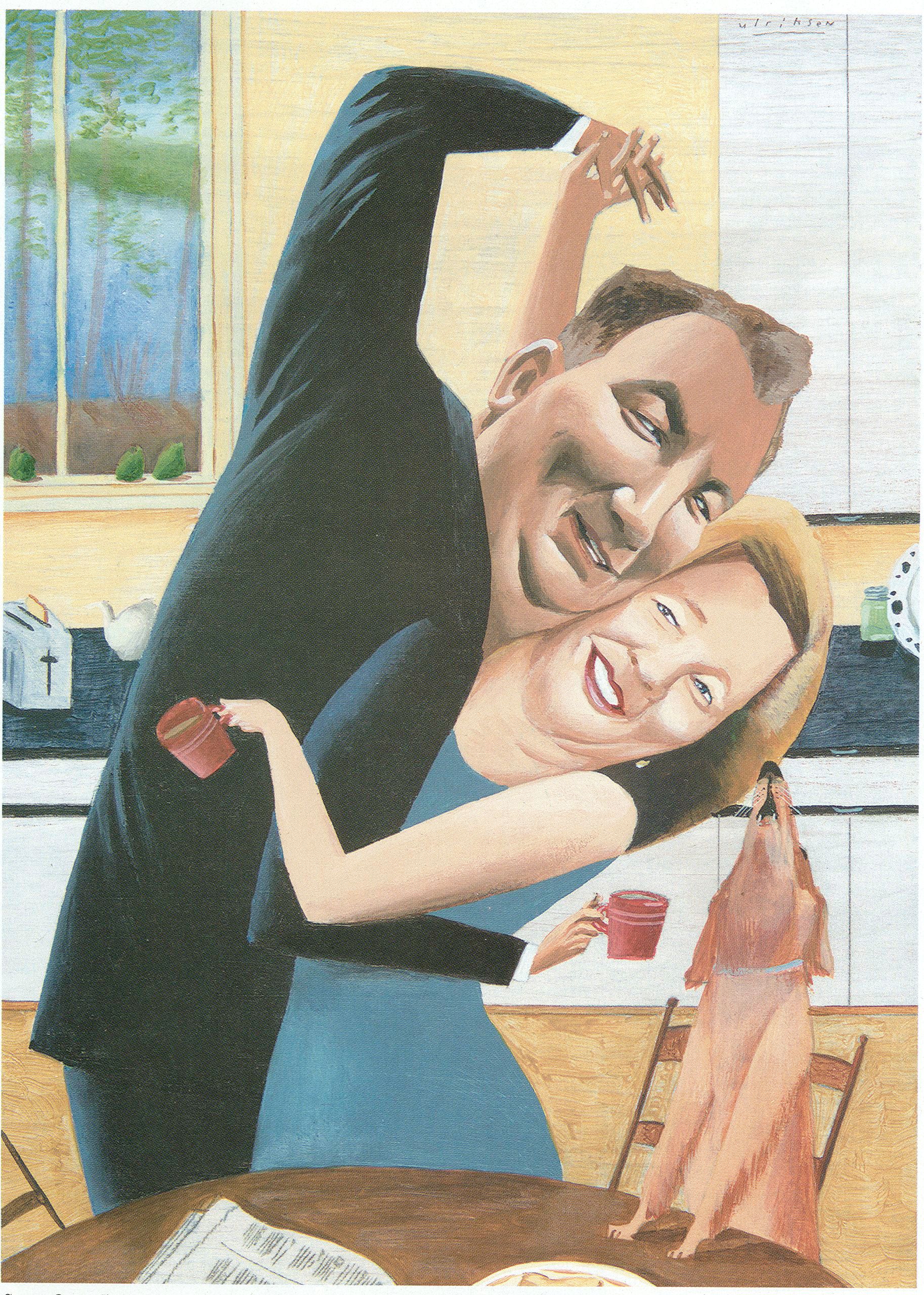

A love story

The New Yorker

As Susan Greer was walking her golden retriever one morning near her home, in Morristown, New Jersey, she heard footsteps behind her. It was just after six, on a warm Saturday in late July of 1998; she liked the quiet and the early-morning light. The footsteps came closer, and then a jogger passed her. He was tall and somewhat heavy, and appeared to be about her age—she was fifty-six. What really caught her attention was his feet. He had no shoes on. It wasn’t like her to say anything to a stranger, but curiosity overcame her, and she asked, “What are you doing jogging in your bare feet?”

The jogger didn’t stop, or even turn around. “I need to know what it feels like to run without shoes,” he shouted, and explained that he was writing a play, and it was set in Africa. Then he was out of earshot. Even though Susan hadn’t glimpsed his face, something about his voice made an impression. She felt sure the same could not be said about her. She hadn’t bothered with any makeup that morning and was wearing old shorts and a T-shirt.

The next morning, she and the dog, Buddy, were again on their walk when a dark-green Lincoln Mark VIII pulled up, and a man inside said hello. She recognized the voice from the previous day. “Why not come to breakfast?” he asked.

Susan saw that the man had an open, friendly face and a direct gaze. “I can’t—I have the dog,” she said.

He seemed genuinely disappointed, so Susan proposed an alternative.

“Why don’t you come have coffee on the patio,” she said. She gave him the address of her town house, just around the corner.

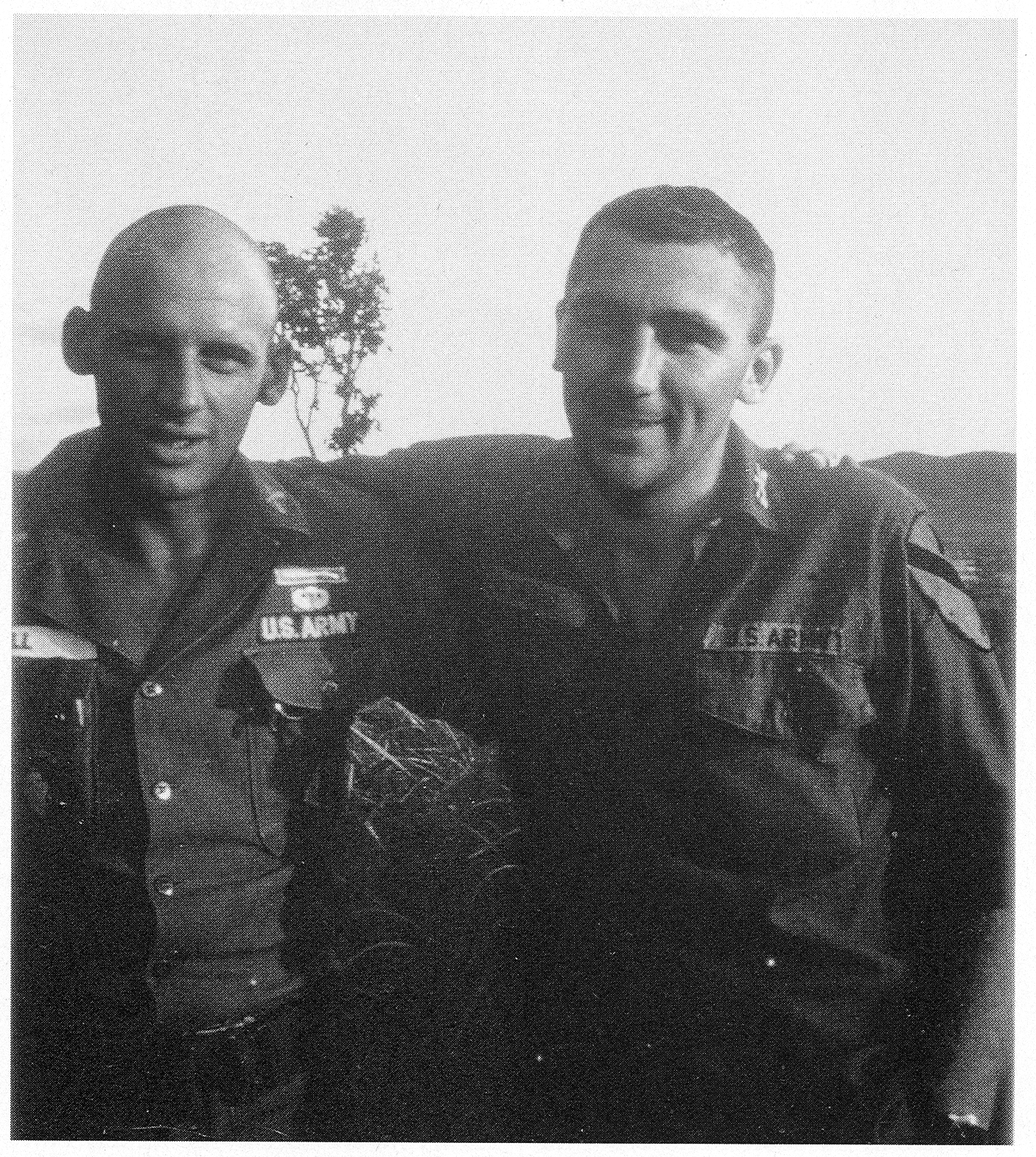

Within the hour, she was pouring him coffee. He said that his name was Rick Rescorla, and he seemed eager to talk—so eager that Susan doubted he was paying much attention to her end of the conversation. (She was later surprised to learn that he remembered everything she’d said.) Rescorla told her that he was divorced, with two children, and was living in the area to be near them. He had been married for many years, but he and his wife had grown apart, and when he felt his children were old enough they’d divorced. His name wasn’t really Rick, he explained, but hardly anyone called him by his given names, Cyril Richard. He had grown up in Hayle, a tiny village in Cornwall, on England’s southwest coast, with his grandparents and his mother, who worked as a housekeeper and companion to the elderly. He’d left Hayle in 1956, when he was sixteen, to join the British military. He’d fought against Communist-backed insurgencies in Cyprus from 1957 to 1960, and in Rhodesia from 1960 to 1963.

These experiences had made him a fierce anti-Communist. The reason he had come to America, he said, was to enlist in the Army, so that he could go to Vietnam. He welcomed the opportunity to join the American cause in Southeast Asia and, for a long time, had never questioned the wisdom or morality of the war. After fighting in Vietnam, he returned to the United States, using his military benefits to study creative writing at the University of Oklahoma, and eventually earning a bachelor’s, a master’s in literature, and a law degree. He had met his former wife there.

Now he was spending his free time trying to write, mainly plays and screenplays. The play he had mentioned the previous morning, “M’kubwa Junction,” was set in Rhodesia, he said, and was based on his time there. Few of the native Rhodesians had worn shoes, which was why he had to feel what it was like to run barefoot. And all his life, he said, he had worked out and kept himself in good shape. He seemed self-conscious about his weight, and explained that his body had swollen because of medical treatments. He had prostate cancer, and the cancer had spread to his bone marrow. He said that he didn’t know how much time he had to live, but, whatever was left, he intended to make the most of it.

As Rescorla was rising to leave, he turned to Susan and said, “I know we are going to be friends forever.” After saying goodbye, she cleared the cups and led Buddy into the house. When she glanced at the kitchen clock, she was surprised to see that it was eleven-thirty; four and a half hours had passed.

Susan made a point of reminding herself that a woman in her fifties with three grown daughters and two failed marriages behind her should have few illusions about romantic prospects. After nursing her mother through a long struggle with Alzheimer’s disease, she had resigned herself to merely going out to dinner occasionally with women friends in similar circumstances. In her mother’s final years, Susan’s town house had been transformed into a virtual nursing home. She also worked full time, as assistant to a dean at Fairleigh Dickinson University, in Madison, New Jersey, and had managed to get her three daughters through college. She had had practically no free time. Still, she had once asked her mother, “Will anyone ever love me again?”

Like many women her age, Susan had been brought up to be a wife and mother, and had never aspired to anything else. An only child, she lived with her parents and grandparents in Glen Ridge in an elegant Colonial house that had once served as George Washington’s headquarters. Her father, a physician, came home after his hospital rounds every day for a formal lunch. The family summered on the Chesapeake Bay, and when she was seventeen her parents took her on a two-month tour of Europe. After graduating from Endicott College, in Massachusetts—at that time a two-year women’s college that was essentially a finishing school—she studied art history in Madrid. She thought of getting a job in Manhattan, but instead married a high-school boyfriend from a similarly affluent family, embarked on a honeymoon tour of Europe that lasted from June to September, and looked forward to leading a conventional upper-middle-class life. Soon she was pregnant with her first child.

1 comment:

And now for the rest of the story...

I know who Rick Rescorla is but it is only through having learned of his daring deeds after 911 that the rest of the story emerged.

Post a Comment