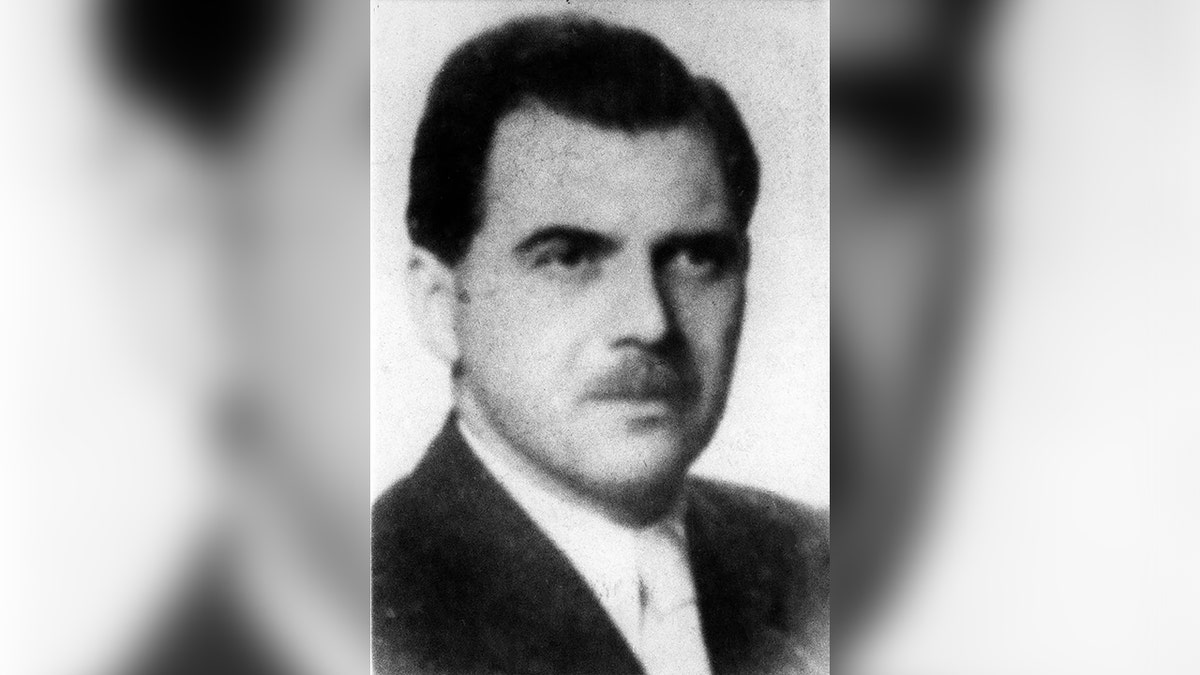

Dr.

Josef Mengele, center, with Richard Baer, left, commandant of

Auschwitz,and Rudolf Hoess, former Auschwitz commandant, outside the

concentration camp in 1944.

Documents revealing how infamous Nazi doctor Josef

Mengele, known as the "Angel of Death," led an open post-war life in

Argentina were found among a massive trove of evidence released and

declassified earlier this year by President Javier Milei.

Mengele

was notorious for his role as a commander in Auschwitz, where he

conducted brutal medical experiments on prisoners, especially twins,

under the guise of scientific research. Eyewitnesses — including some

contained in the declassified Argentine files — describe his extremely

cold-blooded and macabre, sadistic nature, including torturing and

testing on twins in front of one another after sending their parents to

the gas chambers.

An entire binder is dedicated exclusively to following the footsteps of infamous Auschwitz doctor and SS commander Mengele.

The declassified archives show Argentina clearly understood by the

mid- to late 1950s who Mengele was and that he was actually present in

the country. Authorities knew he had entered the country in 1949 using

an Italian passport issued under the name Helmut Gregor, which he used

as the basis for obtaining an official immigrant ID card in 1950.

Argentina’s archival material

sheds light on the networks that sheltered Mengele. Though heavily

fragmented and multilingual — featuring Spanish, German, Portuguese and

English documents — the archive provides a snapshot of how authorities

tracked, archived, mishandled and often took no action regarding the

information they had about one of the world’s most wanted war criminals.

The

collection contains photographs, intelligence notes, immigration

records, surveillance reports and correspondence, reflecting decades of

investigation and efforts to understand the network that helped him move

across Argentina, Paraguay and ultimately Brazil. The presence of

German-language documents indicates the incorporation of foreign

intelligence or materials seized from émigré communities; Portuguese

elements suggest cross-border coordination with Brazilian sources;

English notes point to communication with U.S. or British agencies.

The

files contain an undated press clipping of an Argentine citizen born in

Poland, José Furmanski, who was a victim of Mengele, showing

Argentinian intelligence were aware of the accusations against the Nazi

criminal.

"I met Mengele. I knew him well. I saw him many times in

the Auschwitz camp, with his SS colonel’s uniform and, on top of it,

the white doctor’s coat," says Furmanski in the interview.

An

Argentine file on Josef Mengele, left, and a photo taken by a police

photographer in 1956 in Buenos Aires for Mengele's Argentine

identification document. (General Archives of the Government of Argentina/Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

The interview goes on to explain that Furmanski, who had a twin, gave his vivid testimony of the experiences performed on them. The report labeled Mengele as a pathological sadist.

"He gathered twins of all ages in the camp and subjected them to

experiments that always ended in death. Between the children, the

elderly, and women… what horrors. I saw him separate a mother from her

daughter and send one to certain death. We will never forget," Furmanski

said.

Dozens of scanned images without embedded text and internal

labeling of hundreds of pages signal a systematic effort by Argentine

intelligence to compile a complete personal file of Mengele, including

copies of foreign passports under aliases, photographs of suspected

associates, handwritten operational notes, immigration ledgers or

border-crossing logs, investigative summaries prepared for political

superiors and correspondence between Argentine officers and

international investigators.

The files corroborate Argentina’s

ambiguous postwar position of cooperating with Western democracies,

extremely disjointed bureaucracy, lack of will or understanding

regarding the serious nature of crimes committed by former Nazis in its

territory, and a reluctance by higher-hierarchy authorities to confront

how deeply Nazi fugitives were embedded within the country’s social and

political landscape.

In 1956, trying to expand his business partnership, he obtained a

legalized copy of his original birth certificate from the West German

Embassy in Buenos Aires, requested his ID be judicially amended to

reflect his real biographical data and — surreally — began using his

original legal name, a sign of how safe he felt in Argentina.

Argentine

agencies by this point not only knew who he was, where he lived, and

the fact that he married his brother’s widow and was raising their son,

but also had full details regarding his business interests in the

country. Reports in the files cite a possible visit by Mengele’s father

to Argentina to help him financially, investing in a medical laboratory

business in Buenos Aires.

This

file picture of 1956 shows the WWII war criminal Josef Mengele.

Archaeologists in Berlin have unearthed a large number of human bones

from a site close to where Nazi scientists carried out research on body

parts of death camp victims sent to them by sadistic SS doctor Mengele.

The

overt nature of his life in the country prompted West Germany to issue

an arrest warrant and request his extradition in 1959, which was denied

without further action by a local judge, citing that the request was

unofficially based on "political persecution" of Mengele, which didn't

allow for the case to be taken up.

Despite all the hard evidence accumulated, it is clear that the

information was fragmented among various different agencies that did not

fully communicate with one another. There was also a lack of direct

communication with the country’s presidency and executive branches. This

led to action on the case being decided in a disconnected manner, and

often too late — or after press leaks had already alerted Mengele of

possible concern by authorities — to yield fruitful results. Arrest

warrants, searches, and surveillance requests were often carried out or

decided after the fact, leading to dead ends.

After the 1959 extradition request and with increased international pressure on Argentina, Mengele escaped the country to Paraguay, while his wife and stepson moved to Switzerland.

This

is evident from a memo from the Federal Coordinate Directorate marked

as strictly secret and confidential detailing a search for Mengele and

his business interests dated July 12, 1960 — a point when Mengele had

already left Argentina for Paraguay.

"I bring to the knowledge of

the Chief that from the investigations carried out in order to fulfill

the referenced O.B., it follows that JOSÉ MENGELE, served as a partner

of the medical laboratories ‘FADRO-FARM’ located at Drysdale 3573

Street, in Carapachay, District of Vicente López, and with offices,

since July of this year, at Cramer 860 Street, Capital. The subject,

listed as a medical doctor, was entered into the firm on July 10, 1958,

as a contributing partner of $10,000 pesos in capital, and withdrew from

the partnership in April of 1959," the report stated.

"Since entering Argentina, the subject resided on the property of the

Mengeles, using the name of Dr. GREGOR […], the subject manifested that

he had arrived in Argentina using a different name and distinct from his

profession […]. Thus, it appears that, while maintaining his real name,

the subject belonged to the SS Society […] during which time he

demonstrated being nervous, having stated that during the war he acted

as a physician in the German S.S., in Czechoslovakia, where the Red

Cross labeled him a ‘war criminal.’ He had studied Anthropology and was

known to the Justice in the courts of Nuremberg, especially regarding

the study of skulls and bones, but that union was considered a crime in

National Socialist Germany," the report states about Mengele when, in

the course of changing his name from his fake alias to his real

identity, the Nazi "explained" his motives for originally not using his

real identity, it said.

Argentina’s intelligence community kept following Mengele, mostly

through press reports and contacts with foreign agencies. Mengele

acquired Paraguayan citizenship and was protected by the government of

Paraguayan dictator Alfredo Stroessner, whose family originated in the

same Bavarian town as him.

The archives reveal Mengele entered

Brazil clandestinely at some point in 1960 through the tri-border area

near Paraná state. He was helped by German Brazilian farmers who were

Nazi sympathizers and provided multiple rural safehouses for several

years.

Josef Mengele with an unidentified woman in Brazil in 1975

Though the Argentine files are thin on details and rely

heavily on media clippings at this point, Argentina was aware that

Mengele had adopted the alias Peter Hochbichler, though sometimes he

also used a Portuguese version of his real name — José Mengele. For the

latter part of the 1960s and throughout the 1970s, he began living in

properties belonging to the German Bossert and Stammer families in São

Paulo state, Brazil.

A

police officer stands in front of a cache of Nazi artifacts discovered

in 2017, during a press conference in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Oct. 2,

2019.

Mengele died in 1979 when he suffered a stroke while swimming at sea

in the coastal town of Bertioga. He was buried under the false name of

Wolfgang Gerhardt, but multiple leads led to his body being exhumed and

his remains being positively identified by Brazilian authorities in

1985. DNA testing further confirmed the findings in 1992.

Solly

Boussidan is an international journalist covering Latin America for Fox

News Digital. He has previously covered international affairs, war,

finance and travel for several U.S. and international outlets. He is

currently based in Brazil.