George Shultz Helped Democracy Flourish in Asia

By

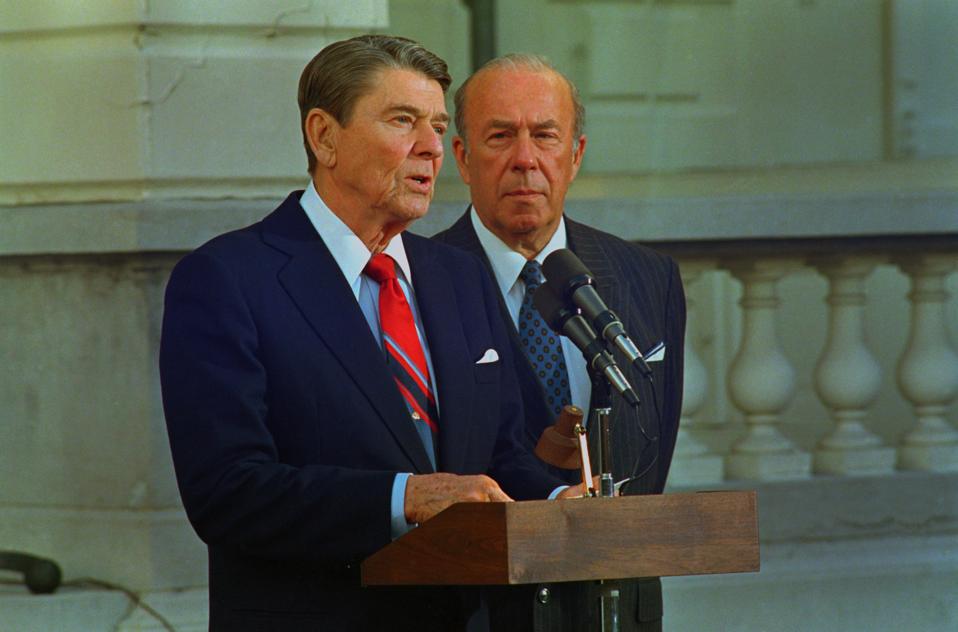

Helping to forge the relationship between President Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev made George Shultz—who turned 100 on Sunday—one of the most consequential secretaries of state of the 20th century. His expert diplomacy led to a peaceful end of the Cold War, bringing freedom to some 400 million Soviet subjects—something that seemed an impossible dream when Reagan took office in 1981. But the triumph of the Reagan-Shultz working relationship went beyond management of the Soviet challenge. The two men helped initiate a democratic wave that swept through Asia and Latin America in the 1980s and ’90s.

Working directly for Mr. Shultz on Asia in the 1980s, I saw how he and Reagan righted a U.S.-China relationship that had become unbalanced. A progression of American officials had forgotten that Beijing needed us far more than we needed them to deal with the Soviets. “I am not here to play cards. I am here to build our bilateral relationship” based on our mutual interests, Mr. Shultz announced during his first visit to China in February 1983. His statement conveyed to China’s leaders that he valued the relationship for the benefits it could bring to our two countries, not because of Chinese hints that they might move closer to the Soviets.

Mr. Shultz also restored balance to the U.S.-China relationship by demonstrating through words and deeds that U.S. allies—particularly Japan—came first, and that he would prefer no deal to a bad one. An incident during that same visit demonstrated his readiness to walk away if pushed too far. At a large luncheon with American businessmen in Beijing, Mr. Shultz’s temper slowly rose as his hosts pressed him with the official Chinese position on issue after issue. Finally, someone asked why American companies weren’t allowed to sell nuclear reactors to China while their European competitors faced no such restrictions. Mr. Shultz replied calmly, and with decided coolness, that the limits were necessary because of “legitimate concern about nuclear proliferation. Your question suggests in rather cavalier fashion that you brush it off. I don’t brush it off.”

Then he walked out, commenting as we left that Chinese intelligence services would report all the pressure he was under from American businessmen. Unspoken was the thought that they would also have to report: George Shultz has steel in his backbone.

A few months ago on these pages Mr. Shultz reflected on how Xi Jinping is turning the clock back to the Maoist economic model while “wrecking Hong Kong” and in the process losing “international trust.” He acknowledged with some obvious pain that “today’s China is different from the one I once worked with constructively.”

By forging a stable relationship with Beijing’s leaders during a better time, Reagan and Mr. Shultz created an opening that allowed for some positive developments. Among the most important was the political transformation of Taiwan from a harshly authoritarian government to history’s first successful Chinese democracy. If the mainland one day returns to the path of reform, Taiwan offers an invaluable example of what people from a Chinese culture can do.

Taiwan is one of those rare instances—Spain under Francisco Franco is arguably another—in which an authoritarian ruler deliberately paved the way for a democratic successor regime. In 1988 Taiwan’s leader Chiang Ching-kuo announced to his inner circle that the “tide is changing” and Taiwan would have to get on the path of reform. He likely had in mind the Soviet Union and two democratic success stories in Asia during Mr. Shultz’s tenure at the State Department.

Following the murder of Philippine opposition leader Benigno Aquino by government agents as he returned home from exile in 1983, American diplomatic strategy focused on the need for institutional reform—political, economic and military—which encouraged Filipinos to believe they could take charge of their own future. And take charge they did. In February 1986, a “people power” revolution led by Aquino’s widow, Corazon, ousted the corrupt and brutal dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos. The following year South Korea also began to follow a democratic path, also with American encouragement.

Dean Acheson once said he never forgot that Harry Truman, who had no college degree, was the president while he, a distinguished lawyer and a Yale and Harvard Law graduate, was a “mere mandarin.” Mr. Shultz similarly gives Reagan the lion’s share of the credit for their extraordinary successes together, disputing the critics who “hammered away” at Reagan’s faults while ignoring his “great achievements.” Mr. Shultz attributes that success to challenging “conventional wisdom” and changing “the national and international agenda on issue after issue.”

In Mr. Shultz’s view, vision and foreign policy must come from the president; the secretary of state’s job is to help shape and then implement that policy. The considerable influence of American diplomacy can’t be brought to bear effectively without that understanding between a president and his secretary of state. Hopefully we’ll have the benefit of George Shultz’s wisdom for many more years. Thankfully, we will always have his example.

No comments:

Post a Comment