What happened to Thomas Friedman?

Once hailed as the world's most influential columnist, Friedman's parroting of Biden administration talking points has raised eyebrows over the years, including during the latest war. As one critic tells Israel Hayom, "He probably believes he is still thinking independently and drawing his own conclusions. It's just a pure coincidence that 100% of his conclusions support the dogmas of the Democratic Party."

Liel Leibovitz

Israel Hayom

Jul11, 2024

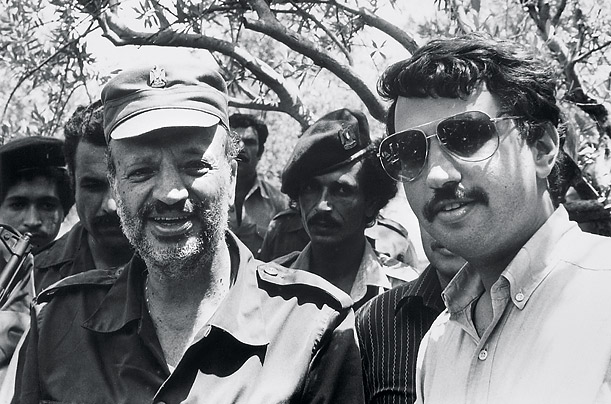

Thomas Friedman (right) stands with Palestinian terrorist Yasser Arafat in Lebanon, circa 1984

Listen to a story, or more accurately, an American Jewish tale: Once upon a time, many years ago, a child was born to a warm Jewish family in Minnesota. Brilliant, ambitious, and clear-eyed, the boy looked around and immediately understood that two obstacles stood between him and glory: First, he lived in the Midwest, while the smart and beautiful people who defined America for themselves clustered in New York or Los Angeles or Boston. And second, he grew up Jewish in a country that still marched to the beat of centuries-old Protestant elites. To reinvent himself, the clever boy realized, he would first need to reinvent America, and, moreover, to create it in his own image.

Who are we talking about? Bob Dylan, born in Duluth, is not a bad guess. But while the iconic singer remained true to the truth even when it wasn't so popular, and was rewarded for his stubbornness and integrity with a Nobel Prize, the second-most important Jew to ever emerge from Minnesota took a different path, which has come to an end now. Thomas Friedman, a close personal friend of President Joe Biden who insisted for years that his friend was sharp as a tack, was forced, in light of the latter's shocking performance in the televised debate against Donald Trump, to admit that Biden is no longer fit to be president and should withdraw from the race.

This admission, which Friedman published in his New York Times column, revealed more about Friedman himself than about his friend in the Oval Office. It exposed, to anyone who still had doubts, that Friedman, one of America's most talented and influential writers of the last four decades, no longer bothers himself with facts or even original ideas, but prints whatever his friends in the political elite decide should be printed. Which says more about the elite than about Friedman: When the parroting reporter himself is called to do damage control, it's a sign that the group that still presumes to dictate the American agenda – and according to every possible poll, does so against the voters' opinion and will – is in deep trouble.

"While Bob Dylan created himself as an American outsider who spoke only in riddles, Thomas Friedman is a professional sycophant who speaks in clichés," David Samuels, a former senior writer at The New York Times Magazine, tells Israel Hayom. "Using his skills as a salesman, he marketed misguided ideas about the Middle East, technology, and China to an audience of Americans uninterested in deep thinking. And like Dylan himself, Friedman can't stop performing. He is the house poet of mediocrity, arrogance, and foolish naivety."

It wasn't always like this. Once, a long time ago, Friedman was a serious, respected, even revered journalist. And to understand how sad his decline is, one needs, as in any tragedy, to understand how inspiring the rise that preceded it was.

Fell in love with the kibbutz

Like many other greats who pushed themselves to fame, Friedman, born in Minneapolis, was orphaned from his father at a young age. The void that undoubtedly remained in his life was filled by two central passions: sports and Israel. As a gifted golfer and a not-so-bad tennis player, young Friedman hoped to be a full-time athlete. But his second love took up more and more space in his heart: Friedman spent long periods in his youth at Kibbutz HaHotrim, which he later defined in one of his books as "one big celebration of Israel's victory in the Six-Day War." And since Friedman didn't want the celebration to ever end, he decided to dedicate his entire career to the Middle East. He completed a bachelor's degree in Mediterranean studies at Brandeis University, a master's degree at Oxford, and after not many years was hired as a foreign correspondent by The New York Times and began covering Operation Peace for the Galile (First Lebanon War).

It did not take long for his editors and readers alike to realize that Tom Friedman was a rare journalistic talent.

"When I taught at Princeton University," Michael Doran, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute and former US deputy secretary of defense under President George W. Bush, tells Israel Hayom, "I made sure to include chapters from his book 'From Beirut to Jerusalem,' as they vividly described the 'zero-sum' logic of Syrian politics under the dictator Hafez al-Assad, logic that led him to raze significant parts of the city of Hama when the 'Muslim Brotherhood' there rebelled against the regime. Friedman reached remote places to which we, his readers, had no access at all, and spoke with interesting people who always had something surprising to tell us about the world."

Even readers who weren't exactly interested in Middle Eastern affairs couldn't ignore Friedman's ability to provide captivating human anecdotes, like the one about the hostess in Beirut whose dinner party was interrupted by repeated bombings, and who finally had to ask her guests if they wanted to eat now or if they preferred to wait for the ceasefire. There was a lot of charm and human warmth in these anecdotes. But there was also something else, something that seeped beneath the surface – a certain rigid worldview that Friedman promoted in every column. Deep down, Friedman repeatedly emphasized in every report, people everywhere in the world want exactly the same thing: to lead a life of peace, tranquility, and economic prosperity, a universal aspiration that everywhere and at all times was disrupted only by a small handful of cynics, who hid their personal interests under the guise of one ideology or another.

The other Israel

This very American approach appealed to Friedman's very American readers. What, then, did those who read Tom Friedman from Beirut and later from Jerusalem learn? Simple: that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict began with Yasser Arafat (Hajj Amin al-Husseini? Don't confuse Friedman with ancient history); that the same conflict is a separate entity that doesn't depend on any external factor (well, so what if there was once such a thing as pan-Arabism that played a crucial role in the region. No need to complicate things too much); that Iran is just a footnote, a regime that exploits geopolitical opportunities, but doesn't really aspire to dominate the region (ignore for a moment Hezbollah, Hamas, the Houthis, and other organizations that Tehran endlessly encourages and finances); that the conflict in the Middle East is mainly about issues of honor and self-definition (religion? What religion exactly are you talking about?); and that while the Palestinians need to stand up and assure Israel that they are for peace, Israel itself has a much bigger challenge: the challenge of giving up any sign of strength.

"Jewish power, Jewish generals, Jewish tanks, Jewish pride" – this is how Friedman describes in his book, with obvious mockery, what he defines as Menachem Begin's supposed pornographic worldview, a view according to which only strength will lead to Israeli survival in the region. For the Jew from Minnesota, the Israelis he fell in love with as a teenager were beautiful and righteous, the people of the Labour kibbutzim and moshavim – not the Likud thugs, not to mention the messianic kippa wearers or God forbid the ultra-Orthodox. One of the most quoted passages in his book likened Israelis and American Jews to a couple who met and fell in love at first sight, until the latter visited the former's home and realized that Israel also has other sides.

"American Jews suddenly found themselves exclaiming to Israelis, 'Hey, I fell in love with Golda Meir. You mean to tell me that Rabbi Meir Kahane is in your family!', Friedman wrote in his first book. "'I went out with Moshe Dayan—you mean to tell me that ultra-Orthodox are in your family! I loved someone who makes deserts green, not someone who breaks Palestinians' bones," he continued.

In 2017 Friedman accused Trump of being a "Chinese agent."

These insights and others like them earned Tom Friedman the Pulitzer Prize in 1983 – the first of three so far – and a regular column in the most influential newspaper in the world. They also secured him the ear of government leaders around the world, who took his words very seriously and conducted foreign policy according to them.

Friedman, says Asaf Romirowsky, a historian and executive director of Scholars for Peace in the Middle East, rose to prominence among decision-makers thanks to "sensational stories at the heart of which is the belief that there is a moral balance between Israel and Fatah."

According to this view, continues Romirowsky, there is no point in talking about "Israeli interests," because Israel and the Palestinians have no independent interests that differ significantly from each other: If all sides are equally guilty in the conflict, then no one is really guilty, and the solution depends only on finding a viable security and economic compromise, which will lead both sides to see how similar they are and how much they can gain, if only they restrain the extremists on both sides.

This logic, the internal logic of the Oslo Accords, became, as Romirowsky notes, the guiding light of those responsible for diplomacy in Washington and European capitals. But the Middle East looked small and dusty to someone with ambitions and talent like Tom Friedman, and in 1995 he was promoted from a journalist reporting from the field to a columnist on global foreign relations.

As always, his timing was perfect: The years were those of the collapse of the Soviet Union, and Friedman the columnist told a story bigger than any he had told before, a global tale with a happy ending, according to which all the dusty obstacles of the old world – wars, beliefs, tribalism, and the likes – were removed, and all that remained was a flat, fast world full of opportunities to get rich. Instead of reports from the field, Friedman, in his columns and books, offered big ideas in service of the globalization celebration. One of the most famous of these is the Golden Arches Theory: "No two countries that both have a McDonald's have ever fought a war against each other," Friedman claimed in a famous column from 1996.

Who is Angelina Jolie?

The theory had its own logic: As globalization creates more and more economic opportunities, it becomes less and less worthwhile for countries to fight each other. Capitalism will bring world peace, Friedman promised, echoing greater thinkers before him, like Adam Smith.

It's not hard to understand why everyone fell in love with the theory, and quickly. For the captains of the global economy, the idea was a promise, not only of enormous enrichment but also of a cloak of moral superiority. For politicians, the idea served as an engine for attractive slogans about a better tomorrow, the kind that pushed young people like Bill Clinton and Tony Blair to the top. And for simple readers, the idea was, how shall we call it, simple – an easy, shiny, and not worrying version of reality after decades of cold and complicated war.

There was just one problem with Friedman's theory: Reality.

NATO's bombing of Belgrade. The American invasion of Panama. The battles in Kashmir between India and Pakistan. Israel and Lebanon. Russia and Georgia. Russia and Ukraine: There's no shortage of examples that disprove not only the bottom line of Friedman's ideas – there are plenty of countries abundant with McDonald's that have fought each other – but also the basic logic underlying them. International companies did not replace nation-states. Economic security did not dim tribal identity. Grudges hundreds or thousands of years old did not dissolve with a single Big Mac order.

But the Friedman train could not be stopped. A profile in The New Yorker magazine from 2008 described to the world Friedman's rise from just another influential journalist to something much bigger: intimate meetings with Bill Gates, frequent briefings with government officials in Washington, dinner parties with movie stars.

But it was important for the boy from Minnesota not to be seen by the world as one who abandoned his Midwestern, all-American roots for power and authority. "I've talked with [Barack] Obama once in my life.," Friedman told The New Yorker writer, forgetting to mention that the president quoted his ideas publicly from time to time, including in a speech at the Gridiron Club in Washington in 2006. In the same article, one of Friedman's friends is interviewed, who told how her friend Tom returned from Davos and told her that he had spoken there with a very beautiful girl. "And what was her name?" the friend asked. "Angelina," Friedman answered innocently, with no idea who Ms. Jolie was.

This naivety was very important to Friedman, as his branding – the source of his power and wealth – was of one who speaks simply and honestly, one who takes supposedly complex matters and explains them in terms anyone can understand. But a brand, as any novice advertiser knows, is only worth something if it manages to attract buyers, and for someone who writes about foreign relations, the buyers are those who run large companies and countries. And it didn't take too long for his ideas to begin to bubble towards open admiration for anyone in power, without any concern for archaic things like conscience or morality or truth.

Here he is, for example, on modern China, in a column from 2009."But when it is led by a reasonably enlightened group of people, as China is today, it can also have great advantages. That one party can just impose the politically difficult but critically important policies needed to move a society forward in the 21st century. It is not an accident that China is committed to overtaking us in electric cars, solar power, energy efficiency, batteries, nuclear power and wind power."

So what if China's carbon dioxide emissions jumped by 80% between 2005 and 2019, according to the U.S. State Department, and so what if Beijing are accused of blatant human rights violations? To Friedman, all this didn't change anything at all. The same goes for Russia: Vladimir Putin – Tom Friedman reassured his readers in a column from December 2001 – is the pragmatic, level-headed, and serious leader the Russian nation has yearned for for ages. The responsible adult who knows that the most important thing in the world is the bottom line of balance sheets, and the man who will be happy with any compromise, as long as it ends with a few more rubles in the average Russian's pocket.

"So keep rootin' for Putin– and hope that he makes it to the front of Russia's last line," he wrote.

Only Biden can. Or not

With this Friedman, who provides ridiculous quotes that innocently celebrate the problem-free victory of the world of startups and technology and gives a pass to any leader who sends the right catchphrases, one could still live. One could even still bear the endless columns against the judicial reform in Israel, which included, outrageously, a call for Joe Biden to intervene in Israel's internal affairs, and to save the only democracy in the Middle East from the ignorant voting public in Israel and its utterly incorrect opinions. Last July, for example, Friedman published a column titled "Only Biden Can Save Israel," in which he argued that Israel of 2023, like Israel of 1973, needs an American airlift of aid, but not of weapons and ammunition but of truth. Israel, Friedman wrote, "needs an urgent resupply of hard truths, something only you [President Biden] can provide."

But even those who could still tolerate the columnist who believes that only Biden can make it clear to Israelis what they really want and need, had to come to terms in recent months with the irrefutable fact: America's most famous writer has entered the third and saddest period of his professional life. In recent years, says Tevi Troy, a presidential historian and the former deputy secretary of health and human services, Friedman has gained so much influence in the Biden administration that he has essentially become a "mouthpiece of the government." Friedman, Troy testified, "gets unlimited access to the White House, and in return shares the administration's perspective." Other sources in Washington reinforced Troy's words, testifying that the relationship between Democratic Party leaders and Friedman has become so symbiotic that it's no longer possible to separate one from the other. And a profile of President Biden in The New Yorker earlier this year mentioned casually that Friedman is one of the few people the president calls frequently.

The man who started his career as a brilliant journalist and continued it as an influential columnist with big and ambitious ideas, is now ending it as a hollow mouthpiece of the elites he dreamed all his life of belonging to, elites whose flaws are increasingly laid bare for all to see.

Want proof? There's none better than the column Friedman was forced to write at the end of June, a column that made waves in American and international media. A bit of background: In recent years, Friedman has often prided himself on his friendship with President Biden and his closeness to the administration. When world leaders crowded into Davos, Switzerland in January, for example, Friedman and his friend Antony Blinken sat down for a public conversation on stage and sounded more like two friends late at night at a bar than the secretary of state and the most respected journalist of his generation. And yet, Friedman, the man who once prided himself on straight and reliable reporting from the field, never questioned Biden's competence. He continued to encourage the president even as the latter's mental state appeared increasingly fragile. He continued to write columns claiming that the 81-year-old man in the Oval Office is a brilliant statesman working tirelessly on the "Biden Doctrine," one that will bring peace to the Middle East – Friedman argued in a column earlier this year – through American insistence on the immediate establishment of a Palestinian state. And if Biden is not re-elected, Friedman cried in another column, we can expect an immediate global catastrophe.

And then Joe made his way to the television studio, took his place on the debate stage with Trump, and proved what was already clear as day to anyone who had looked at the president without bias in recent months – or in recent years: Biden does not have the cognitive skills required for the office he aspires to be re-elected to.

The debate put Friedman in a difficult position. Column after column head painted the president as a once-in-a-generation leader, a brilliant statesman without whom the world is a step away from disaster. Column after column after column he poured contempt, mainly on Trump and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, and promised his readers that only Biden can curb the destructive appetite of such dangerous leaders.

Just this past February, he wrote that Biden is "a president who grew up in the Cold War and built on a bedrock of American values and interests that have served us well since we entered World War II." In contrast, Trump "behaves as if he learned his world affairs not at Wharton but by watching World Wrestling Entertainment." And in another column that same month, Friedman warned Netanyahu that since his post war plan is "essentially says to the world that Israel now intends to occupy both the West Bank and Gaza indefinitely," he shouldn't be surprised if the whole world "will edge away and the Biden team will start to look hapless."

Thomas Friedman said all this. And in almost every column, he repeated and emphasized that only President Biden can solve the conflict. At no point did Friedman admit, even in a word, that the man to whom he is so close is deteriorating.

Until the debate came, and Friedman was forced to write a column in which he calls on his friend the president to step down. Which proved what many have long thought: that the esteemed columnist now spends his days parroting the messages that come to him from the White House.

Took the bait

This realization is now seeping in even among those who were previously Friedman's admirers. "He has abandoned the central roles of any journalist – to tell the truth, to ask hard questions that our political orthodoxies forbid us to ask, and to stand his ground regardless of the cost," says Doran. "I won't speculate about who and how Tom Friedman was tempted to abandon these qualities, which he once had, but I have no doubt that he was tempted indeed. Friedman is probably unaware that he has become a mouthpiece for the administration. He probably believes he is still thinking independently and drawing his own conclusions. It's just a pure coincidence that 100% of his conclusions support the dogmas of the Democratic Party."

This partisan worldview, Doran concludes, points to much more than the lack of professional integrity of one journalist, but to a much bigger problem with the worldview that Friedman is asked to promote – a worldview of a liberal elite that has lost all grip on reality. Friedman, Doran explains, promotes a theory according to which Biden is trying to establish a regional coalition against Iran, a coalition whose entire existence is in doubt only because of Netanyahu's insistence on not agreeing to the establishment of a Palestinian state that would give the Palestinian Authority control over Gaza. And this theory, Doran continues, suffers from clear illogic.

"First, the Palestinian Authority has failed to take control of the West Bank, so how exactly are they supposed to control Gaza, from which Hamas expelled them in 2007? Second, doesn't Biden's policy, which insists on ending the war immediately and in a way that will leave Hamas with some control over the territory, make the idea of a new order in Gaza even more absurd? And finally, doesn't the fact that Biden is working to find diplomatic solutions with the Iranians in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen refute the idea that the administration is somehow trying to build a coalition to fight Iran? These questions have never bothered Thomas Friedman. And for this reason, I now read him as one reads columnists in the Russian, Chinese, and Arab press: no longer to learn new and surprising things about the world, but to see what the regime wants me to believe."

No comments:

Post a Comment