Israeli Opposition’s Hostile Rhetoric ‘Impedes Compromise on Judicial Reform’

While experts differ sharply on the Israeli government’s reform plan, all agree that extreme discourse is clouding the issue.

Tel Aviv Mayor Ron Huldai made headlines on Monday when he said that countries become dictatorships through the democratic process but “do not become democratic again except through bloodshed.” Vying with Huldai was former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert. Nodding toward the Knesset walls, he said, “It’s good to see 100,000 people here, but that’s not what will lead the real fight. The real fight will break through these fences and take us into a real war.”

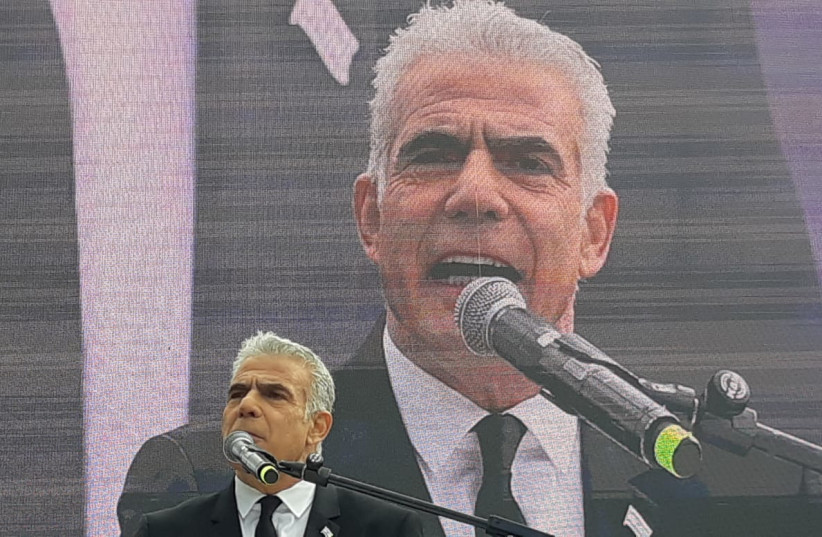

Opposition Leader Yair Lapid of the Yesh Atid Party told an estimated 60,000 protesters at the Knesset on Monday that “a corrupt extremist government wants to destroy the country at record speed.”

National Unity Party leader Benny Gantz told the crowd that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is “destroying Israeli society from within.”

Noteworthy is that these are all mainstream leaders, not fringe elements.

Netanyahu on Monday called on the opposition to lower the flames following the protest outside the Knesset and a tempestuous Knesset committee meeting, in which opposition members jumped on tables and had to be forcibly expelled.

“Stop deliberately dragging the country into anarchy. … Show responsibility and leadership, because you’re doing the exact opposite,” he said.

The opposition shows no signs of stopping or changing its tone, however. According to Avi Bell, professor of law at the University of San Diego and Bar-Ilan University, that’s because it’s thoroughly invested in maintaining the status quo.

“From the outset, the opposition to judicial reform has rested on demagoguery and veiled threats of violence,” said Bell, noting that at times it has descended into self-parody. “Just in recent days, academics published new mass petitions claiming judicial reform would kill cancer patients and destroy nature itself,” he said.

“Years ago, when the judiciary first launched its ‘constitutional revolution,’ there was a fairly rational debate over the proper judicial role and whether judicial super-activism was compatible with Israel’s democratic system of parliamentary supremacy,” explained Bell. “The judiciary proceeded to ignore that debate and do what it wanted, rendering the debate moot,” he added.

“In recent years, rational debate has withered away. Supporters of judicial supremacy [the current opponents of judicial reform] have seen no reason to debate an issue they already won, and long ago substituted bullying and gaslighting for persuasion. The current fight against judicial reform is a naked battle to retain illegitimately seized power, so naturally the rhetorical strategy of anti-reformers is intimidation, threats and hyperbole,” he continued.

‘Regime change’ claims

Naomi Chazan, professor emerita of political science at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and a former Knesset member for the Meretz Party, told JNS that both sides of the debate have been guilty of extreme rhetoric. Calling all opponents of reform “anarchists” is but one example, she said.

A staunch opponent of reform, Chazan rejects even the term.

“’Reform’ assumes a mild tweaking here and there. This is a massive change and politicization of the judiciary, putting it under the hands of politicians,” she said. She suggests using instead the term “revolution,” adding, “Some people call it a judicial putsch.” According to Chazan, the judicial changes being proposed are just “one element” in a much larger process toward “regime change.”

“It’s a fundamental change in the structure of government, [and] to narrow it to the issue of judicial reform is to miss a lot of the elements,” she said. According to Chazan, these elements include discrimination against women and the strengthening of rabbinical courts.

While Chazan didn’t agree with those claiming that Israel will become a dictatorship if the reforms are implemented—a refrain commonly heard from opposition leaders—she said that the changes do entail “a stripping of the democratic essentials of the regime.”

Is there a middle ground?

Itzhak Bam, an Israeli attorney specializing in areas of criminal and administrative law, human rights and freedom of expression, told JNS that despite appearances, there is room for compromise. He noted that a group of jurists, including former Deputy Attorney General Raz Nizri and Netta Barak-Corren, a professor of constitutional law at Hebrew University, are “ready for dialogue and have positive proposals.”

However, he admitted, such voices are in the minority.

“Unfortunately, most others have taken positions that disengage them from the dialogue. When you say any reform will be the end of democracy and bring about dictatorship, the other side understands a) that it’s nonsense, and b) that you’re not coming for dialogue and compromise, you’re coming to fight,” he said.

Indeed, government gestures toward compromise have so far been rejected by the opposition.

On Wednesday, the government delayed bills linked to the reform plan, “in order to encourage dialogue,” though it noted that a vote on judicial legislation would take place on Feb. 20. Justice Minister Yariv Levin and Knesset Constitution, Law and Justice Committee chairman Simcha Rothman, the two key figures guiding the judicial reforms through the legislative process, requested that Lapid and Gantz meet with them at the president’s residence on Monday, an offer that was rebuffed.

Opposition figures are demanding that the progress of the reform bills through the Knesset be frozen as a precondition to any talks, which the coalition has adamantly refused to do.

Fuel on the fire

Coalition members complain that the country’s mainstream media is only adding fuels to the fire. Rothman expressed his frustration during a heated interview with Channel 13 on Monday, telling the anchors that he was surprised they wanted an actual politician on the show given how their reporters spout political opinions instead of news.

Attorney Bam said he supports free speech and if the media wants to insert their politics into the news that’s their right, just so long as Israel stops both regulating and subsidizing television and radio so that other voices can be heard.

“It’s not new that the media takes sides,” Bam said. “If they want to mix journalism and political activism, it’s alright. I think it is part of freedom of speech. But on two conditions: first, no one has a monopoly over the microphone—anyone can open a TV or radio channel. Second, no one is compelled to pay for content. If they want to put their politics in the news, fine, but I don’t want to fund it.”

Bam strongly favors the reform plan, calling it the “most important achievement of the right wing in the last 20 years at least,” and believes the protests won’t stop it.

“While it upsets a minority that feels the rug is being pulled out from under it, the majority, for almost three decades, feels that the Supreme Court has been oppressing them and imposing justices’ political values through court decisions—values that are not held by the majority.”

The government appears determined to carry out the reforms. Netanyahu has dismissed the “hue and cry” against the initiative as a movie he’s seen before, referring to similar political uproars connected to successful economic policies he’s implemented in the past. The dire predictions of naysayers never came to fruition then, either, he noted.

According to professor Bell, the reform’s effect will be the exact opposite of that forecast by its critics, such as Chazan.

“In whatever form the reforms are adopted, they will restore Israel’s democracy, make Israel more like the rest of the democratic world, and end Israel’s anomalous status as the only country ruled by self-appointed judges and lawyers with unlimited power and no accountability,” he said.

No comments:

Post a Comment