Smithsonian magazine takes in-depth look at in-progress Ike Dike in Texas

$57 billion project would require civil and political engineering to pull off

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/Galveston-IkeDike.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6b/94/6b94d2d5-869c-496b-9baf-585daed9bf0e/julaug2024_k15_ikedikegalveston.jpg)

The one that the so-called “Ike Dike,” still at least 20 years away, is designed to stop?

Now that the first round of federal funding for the inflation-adjusted $57 billion project -- originally projected to cost $34 billion -- has finally begun to flow, Smithsonian magazine has published an in-depth article on the Ike Dike, better known in governmental circles as the Coastal Texas Project. Texas-based writer Xander Peters provides a detailed account of how the project left the drawing board and the many interlocking components of the plan.

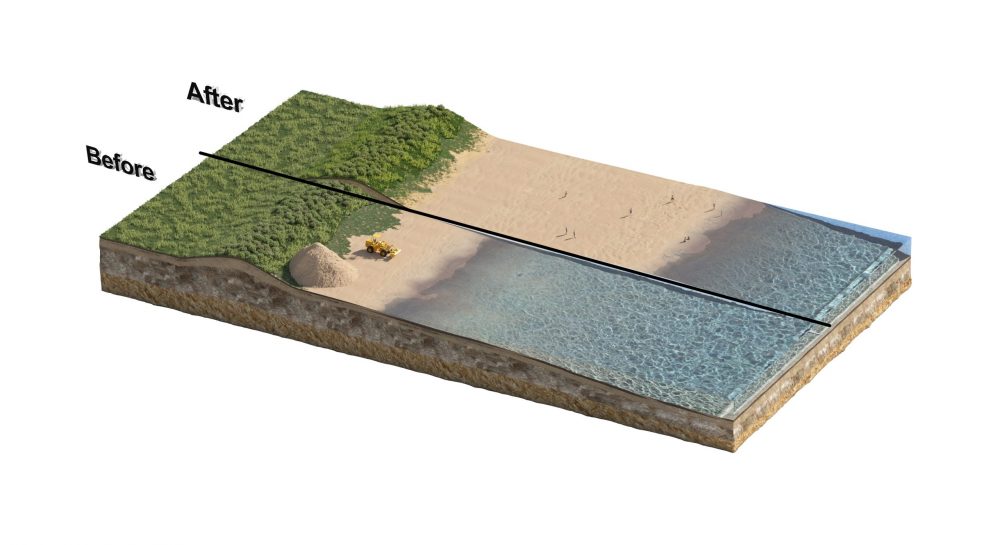

Highlights include 25 miles of additional dunes along Bolivar Peninsula’s beaches and 18 more on western Galveston Island; narrow channels between the dunes that would aid flood runoff and shelter wildlife; 36 sea-blocking gates between the island and peninsula, including two at the mouth of the Houston Ship Channel that would be 650 feet wide and 82 feet tall; and 14-foot reinforced concrete flood walls around Galveston’s central business district, able to withstand all but the deadliest storm surge.

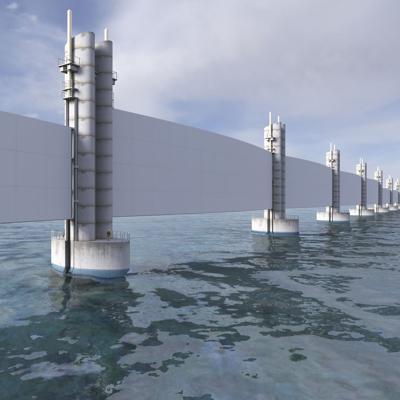

The Ike Dike's floodgates at the mouth of the Houston Ship Channel would be 82 feet high and 650 feet wide.

Several vertical lift gates would help guard against catastrophic storm surges.

In describing the project, Peters introduces readers to a motley cast of characters including Kelly Burks-Copes, project director for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; William Merrell, the Texas A&M-Galveston professor and historical novelist who dreamed up the centerpiece of the plan, a “coastal spine” based around a 1950s flood-control project he saw in the Netherlands; and Jim Blackburn, the former Rice University professor and dissenting environmentalist whose concerns about the project’s impact on the coastal wetlands get full consideration.

“If the plan succeeds,” Peters writes, “it could forever change the way Americans mitigate storm damage.”

Even Burks-Copes, who is postponing her retirement to get the Ike Dike off the ground, tells Peters she initially “had difficulty grasping the scope and ambition of the Texas project.” Its success could be the public-works deal of the century, considering the ballooning damage estimates for Gulf hurricanes since 2000—$30 billion for Ike, $125 billion for Harvey and Katrina, $112.9 for Ian in 2022. And, as any meteorologist will tell you, the frequency of big storms is only growing.

“If you get [the dike] in place,” Burks-Copes says. “It’s paid for in one storm.”

The plan also calls for 25 miles of additional dunes on Bolivar Peninsula and 18 more on western Galveston Island

Above everything else, Peters does an excellent job of laying out the consequences of not building the project: “When it comes to the Texas coast, a massive storm would affect every single state in the country,” he writes. “Oil and gas prices would soar. And even a temporary closure of the Port of Houston would send shock waves through not only the domestic but also the global economy.”

So if the Ike Dike comes to fruition, it would be an unalloyed triumph of both civil and political engineering. Burks-Copes and the corps estimate it will be another seven years for the final designs to be ready, and then 12 more for the actual construction. At least.

If that sounds far-fetched, it’s actually not; timetables for similar projects in Europe range between 30 and 50 years, Peters notes. But the federal government and State of Texas, which are slated to split the project’s cost 65-35, are going to have to cooperate long enough, and well enough, for it to get built. That’s not exactly something we can take for granted these days at all.

No comments:

Post a Comment